This year, the Investment Committee and I have received more questions about the Federal budget deficit and accumulated debt than the rest of my career combined. For good reason.

The public debt has exploded by over $10 trillion since the end of 2019.

While much of the increase was due to pandemic-related relief and stimulus efforts, Washington continues to demonstrate an almost-shocking inability to live within its means. For instance, the total public debt outstanding grew an almost $2.5 trillion in 2023. This after an additional $1.8 trillion in red ink in 2022.

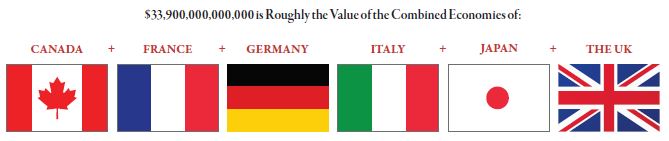

At an estimated $33.9 trillion and counting, is there any end in sight to the mountain of debt Washington is amassing? Surely, this will have a negative impact on the economy moving forward, right?

Before I answer that last question, it is important to understand on what the U.S. Treasury currently spends money and how it intends to spend money in the future. For that, we need to take a look inside the administration’s proposed budgets.

As of November 2023 it costs $169 billion to maintain the debt, which is 16% of the total federal spending.

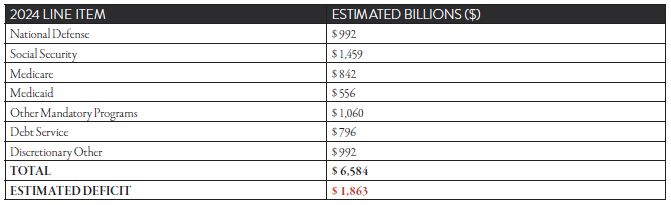

Page 137 (out of 176) in the most recent budget shows “top of the house” outlays and receipts. In 2024, the White House is estimating the Treasury will take in $4.721 trillion and spend $6.584 trillion.

That would result in an annual deficit of $1.863 trillion for 2024.

Now, consider that revenue figure, $4.721 trillion.

- To put it into perspective, that number is greater than the IMF’s 2023 estimate for the nominal Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for South America, the entire continent in aggregate.

- If that doesn’t seem like much, it is also greater than the nominal GDP of any of the other countries in the G7.

That is a lot of money, and we still can’t make ends meet. Why?

HOW THE DEBT ACCUMULATES

To answer that question, take a look at the table below:

If you are curious what “other mandatory programs” are, page 140 outlines them in excruciating detail. While some of these might seem like so much fluff to many, they all represent promises Washington has made and intends to fulfill. For “discretionary” outlays, please take a look at Table S.8 on page 164.

As for the rest of it, Washington can eliminate all discretionary expenditure outside of the National Defense and still run an annual deficit of roughly $900 billion.

“Stated simply, the Federal Government could effectively shut down all Cabinet Departments and major agencies, and the Treasury still wouldn’t have anywhere close to enough money to balance the budget.”

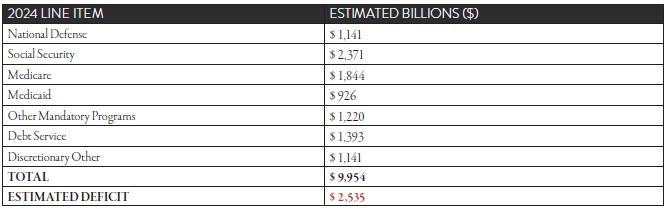

If that seems frustrating, consider how the numbers might look in 2033:

I’ve got news for you. Given current levels of spending, and the apparent lack of concern about it, we will be lucky if the deficit is only $2.5 trillion in 2033. After all, the vast majority of the estimated increases in payouts are in Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid and the Debt Service.

In fact, ‘discretionary other’ shrinks to less than 12% of all outlays in 2033 from 15% in 2024. Exclude them from the budget in the future, and the Treasury will still have a, get this, $1.4 trillion annual deficit.

So, the $64,000 Question is this: what do you want to cut?

- Defense? This doesn’t seem terribly likely with all of the turmoil in the world.

- Social Security and Medicare? Oh boy, who has the nerve to tackle those two sacred cows? Further, older people tend to vote, you know?

- Medicaid? That sort of seems a little mean spirited, doesn’t it?

- The debt service? While that might be tempting for many, defaulting on the public debt would cause a massive financial system collapse and global recession.

It’s daunting, and undoubtedly the reason few of our elected officials seem to be taking this problem very seriously. It is too overwhelming and would be extremely unpopular to tackle. Besides, we seem to be able to finance our deficit quite nicely, all things considered.

Therein lies the problem.

FINANCING THE DEBT

For years, Washington has been able to borrow for essentially free, less than the accepted rates of inflation. So, there was little reason not to do so. Now, however, interest rates have normalized, and the folks on Capitol Hill will be facing a new reality, whether they like it or not.

Borrowing money is going to be more expensive moving forward, which should limit the amount the Treasury will be able to borrow at favorable terms.

As a result, you can expect those ‘other mandatory programs’ and ‘discretionary other’ expenditures to grow even slower than the current budget projects. Obviously, this will have an impact on how much the Federal government will be able to purchase or spend on so-called pet projects and pork.

In other words, it means Washington won’t be as forthcoming with fiscal stimuli or largesse as it has been over the last 15 years.

“Put another way, we can expect the government to shrink as a percentage of GDP even as annual deficits go through the roof.”

I understand this might not make any sense. However, the G variable of the GDP equation represents what the government actually purchases or invests back into infrastructure. It doesn’t reflect Social Security payments, salaries, etc., which are included in the C (consumer) variable.

GDP = Private Consumption + Gross Private Investment + Government Investment + Government Spending + (Exports – Imports) Or: (C+ I + G +/- Net Exports)

As a result, we can expect the government to officially add less to the overall GDP equation than it has in recent memory. It just simply won’t have the means to buy as much stuff because the bulk of the money is going to entitlement and other mandatory program payments to individuals.

Voila. Which is the primary reason how all of this debt is going to drag down the economy. Fiscal stimuli will, or should, be less in the future, especially in relative terms. Of course, this assumes there isn’t a major global conflagration which would require a military mobilization.

So, what can be done?

Over the next decade, there will be no shortage of proposed tax schemes proffered to raise additional receipts for Washington. All of them will be the equivalent of “pushing on a string.” A not terribly exhaustive study of our nation’s economic history suggests tax receipts tend to go up when the economy expands. The greater the economic growth, the greater the revenue in Washington.

As such, the best way to make a dent in the budget deficit is grow the domestic economy as rapidly as is possible. This would require unfettering the private sector in a way which might be socially distasteful to many. Untold regulations would have to go out the window. We would need to be more realistic about how mandates actually impact economic decision making.

Frankly, we would have to have more people in the halls of power who have run a business, had to make a payroll and actually took risks with their own capital. After all, it is much easier to make decisions about other people’s money than it is your own.

“Personally, I believe a logical first step would be to eliminate the capital gains tax, and I mean scrap it. It is little more than a capital constraint, as it negatively impacts the free flow of investment throughout the economy. Essentially, it effectively forces investors to hold on to underperforming assets when there are more attractive alternatives.”

How can that possibly be good for economic activity? Intuitively, it isn’t.

Admittedly, there is little chance of this happening. However, a meaningful reduction in the capital gains tax rate would allow money to flow to its highest and best use and potentially even raise revenue for Washington. It would be a good start, even if it would be politically unpopular for many.

In the end, unfortunately, there doesn’t seem to be an end in sight to our deficits. Fortunately, they likely won’t crush the economy as much as constrain it. If we are serious about reducing them, we need to be serious about growing the economy. Putting more regulations, constraints and higher taxes on both businesses and capital is not the solution, and never was.

That is what I tell people when they ask me about the public debt.

This content is part of our quarterly outlook and overview. For more of our view on this quarter’s economic overview, inflation, bonds, equities and allocation read our entire Annual 2023 Macro & Market Perspectives.

The opinions expressed within this report are those of the Investment Committee as of the date published. They are subject to change without notice, and do not necessarily reflect the views of Oakworth Capital Bank, its directors, shareholders or employees.