After some political theatrics in Washington, D.C., earlier this year, lawmakers finally agreed to raise the debt ceiling and avoid a catastrophic U.S. debt default that would have had unseen economic effects. While politicians may have been confident that a deal would be reached, credit rating agencies were not so convinced. Fitch soon after downgraded the U.S. Long-Term Foreign-Currency Issuer Default Rating from AAA to AA+.

While this may not seem like a big deal, the downgrade comes as many questions loom on the horizon for fiscal policy makers.

Why the massive amount of debt accumulation in such a short amount of time?

The purpose of the federal government, according to the U.S. Constitution, is “to establish Justice, ensure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity.” To achieve this goal, the government funds social programs, subsidizes important economic drivers, and spends money on public projects. To pay for this, the government uses tax revenue.

But in times of war and significant hardship (such as WWII and COVID-19) this revenue isn’t enough to foot the bill. This means the government must borrow money, which it can do in two ways: either through selling marketable securities to the public (such as treasuries or other loan structures) or through intergovernmental borrowing (such as the Social Security pool).

When did it all begin?

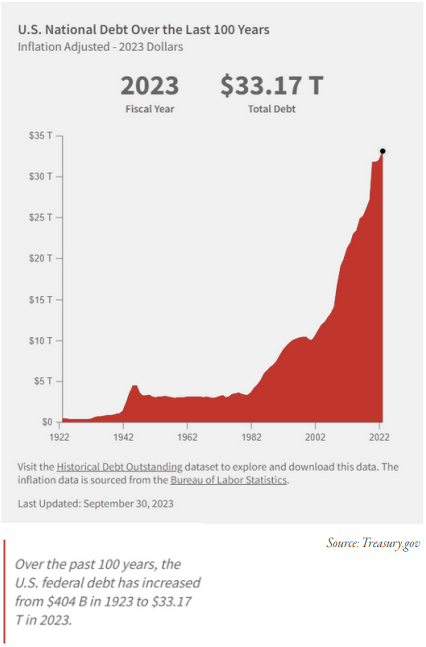

Federal debt started accumulating shortly after the birth of the nation, as U.S. revolutionaries had to pay for equipment to fight the British.

- As early as 1791, the S. national debt hit a level of $75 million. To ensure the U.S. government would pay for this debt and assist a post-Revolutionary War economy, Alexander Hamilton created the United States Treasury, as well as the National Bank of the United States.

- The national debt fell until Thomas Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase. Debt then began to accumulate once again until Andrew Jackson paid off all interest-bearing debt in 1835 by liquidating the Second National Bank.

- The Civil War (1861) plunged the nation back into debt, which continued to steadily increase with the onset of the Great Depression, WWI and At the end of WWII, the national debt was somewhere in the range of $260 billion, with this number increasing to a staggering $33 trillion in the present day.

How did we end up here? If the last budget surplus was in 2001, how did national debt get so out of hand?

THE DOT-COM BUBBLE

Starting in 2000, Americans faced new economic and social challenges. The dot-com bubble imploded, which saw millions of dollars in online growth stocks evaporate overnight. Internet companies were burning through cash at an unseemly rate. When paired with federal funds rate increases, most of these companies had to pack up shop and close after once enjoying huge valuations. The government immediately began spending again, in an attempt to offset the economic downturn brought on by the crash.

9/11

Soon after, the world would change forever as members from the Al-Qaeda terrorist group committed the deadliest terrorist attack ever seen on U.S. soil on September 11, 2001. This exacerbated turmoil in domestic markets, causing another sharp drop in equity prices. Government spending once again increased as rebuilding efforts went into effect, but this also led to various new programs being formed to dissuade or prevent attacks like this again, which required additional funding. The TSA was created in 2002 with a budget of $1.3 billion. By 2003 that budget had increased to $4.8 billion. Additionally, Congress fought to seek justice for the attacks on America, and began military operations in Afghanistan in October 2001. Estimates by Brown University have put the total cost of U.S. military operations in the Middle East at around $8 trillion.

THE GREAT RECESSION

To briefly summarize, the federal funds rate steadily increased in 2006 and 2007, and homeowners with adjustable-rate mortgages (almost a third of all Americans) saw their monthly payments skyrocket. To compound this, the largest concentration of these adjustable-rate mortgage holders was in the subprime space (issued to borrowers with less-than-ideal credit). Many Americans defaulted on their mortgage payments, rupturing many mortgage-backed securities and other collateralized debt obligations. Banks that had significant exposure to these now-defunct mortgage-backed securities and CDOs faced solvency issues. To prevent the U.S. from sliding into economic catastrophe, Congress issued emergency funding to keep some of these banks afloat. It created the Troubled Asset Relief Program, which was a bailout for these banks, with a price tag of $700 billion.

COVID-19

COVID-19

Fast forward to 2020. From about 2009 to 2020, the country saw unparalleled growth and equity appreciation thanks, in part, to a historically low Federal Funds rate. The S&P 500 returned 257% over this time frame, with no apparent end in sight. Until the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Not since the Spanish Flu of 1918 was there such chaos caused by an outbreak of a viral disease. The economic impact of Covid-19 was immense, and investors panicked. Beginning in March 2020, the S&P 500 index fell more than 16% over the course of the month.

Several measures were taken in response to the pandemic:

- The federal government pass the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act on March 6, providing $8.3 billion in aid to fight the pandemic. Tax revenues, however, had actually decreased, so this was piled onto the national debt.

- The Families First Coronavirus Response Act was passed ($192 billion), along with the CARES act ($1.8 trillion), adding to the increasing mountain of

- Then there was the Payment Protection Program or PPP, another $800 billion, in which only about 35% went directly to workers.

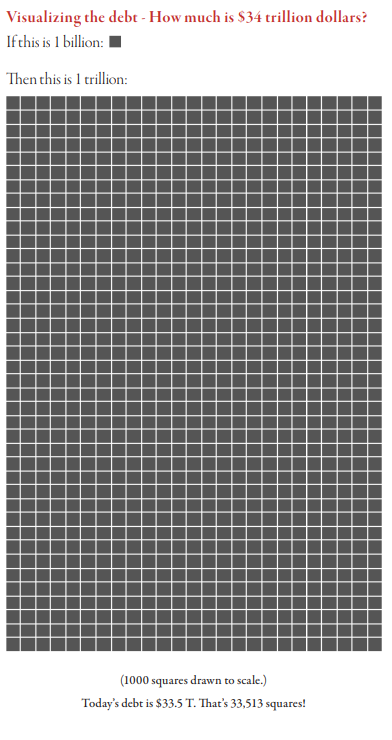

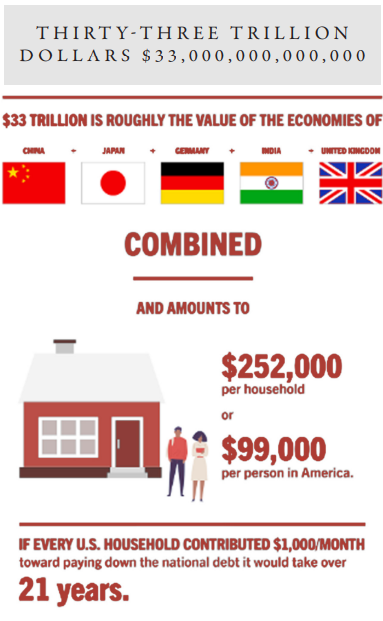

Federal spending increased by 45% in the 2020 fiscal year. This brings us right up to present day, where we can see the total national debt nearing …. drumroll please …. $33 trillion!

When interest rates remain low overtime, interest expense on the debt paid by the federal government will remain stable, even as the federal debt increases. As interest rates increase, the cost of maintaining the national debt also increases.

Where do we go from here?

Like many things in politics, it’s just not that simple. Plenty of politicians have tried to reign in this spending over the years, but legislators seem to focus on what gets them reelected, and cutting social programs is a surefire way to lose to a new candidacy come November. So, what would be a morally responsible way to solve the debt crisis? Well, there are a few ways to look at it.

- The first would be to exponentially grow the tax This involves holding interest rates lower to spur significant growth in both corporate earnings, and consumer spending.

- To do this though, the government would have to stop the increases in spending each year, which it seemingly is unable or unwilling to do.

- The second option is to broadly reduce spending across the board.

How do we cut spending?

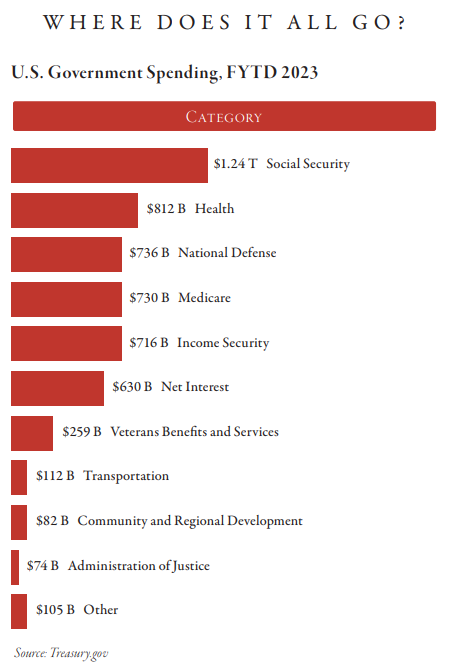

If Congress decided to cut spending by 26% across all programs tomorrow, we would be able to balance the budget.

- Defense: While some might say this is an easy fix, others might argue that we need to keep up defense spending to protect S. interests overseas, and take care of said veterans. That means cutting all spending, excluding defense and Veterans Affairs, by 33%. This is not a huge leap in cuts, but it quickly begins to add up.

- Social Security: Who wants to cut down income checks retirees receive? With that argument in play, we would have to cut spending by 51% if we didn’t want to touch defense, Veterans Affairs, or Social Security. Fifty-one percent is significant, and we would really start to feel the economic impacts of the reduced spending.

- Medicare: In an ideal world we would want to keep Medicare, too, right? So without touching defense, Veterans Affairs, Social Security OR Medicare, we would have to cut spending by a whopping 85%.

- Education: Education is a long-term investment, and cutting programs in this category would have significant consequences down the road.

What does a realistic plan for moving forward look like? Taking everything into account, we can see that the most practical approach would be somewhere in between the two options listed above, with lawmakers coming up with a concerted bipartisan effort to grow the tax base and reduce wasteful spending. Politicians owe it to their constituents to act as careful stewards of our tax dollars, and so far, it seems they have failed us. The current path we are on is unsustainable – the interest on our debt alone is estimated to cost $808 billion (or 15% of the federal budget) in 2023. Until then, we will have to deal with the theatrics of arguing about a debt ceiling raise every few years, even though it is in everyone’s best interest for the United States to pay its debts. Maybe Congress can come together to figure out an answer.

Did I mention the possible government shutdown?

We’ll see what happens in November.

How is the debt ceiling different from a government shutdown? Government shutdowns occur when annual funding for ongoing government operations expires, and Congress does not renew it in time.

This content is part of our quarterly outlook and overview. For more of our view on this quarter’s economic overview, inflation, bonds, equities and allocation read our entire 3rd Quarter 2023 Macro & Market Perspectives.

The opinions expressed within this report are those of the Investment Committee as of the date published. They are subject to change without notice, and do not necessarily reflect the views of Oakworth Capital Bank, its directors, shareholders or employees.