It seems all anyone has wanted to talk about in the last year is inflation. Before this most recent Federal Reserve intervention – prior to 2020 – we lived in a fantasy-like economy set in the midst of a historically long bull market run. The overnight lending rate set by the Federal Reserve hovered around 0% to 0.1%. Money was cheaper to borrow than at almost any point in American history. While it was a good time for many Americans, and business was booming, eventually the bill came due.

Fast forward to today: The last time inflation was as high as it was in 2022, Jimmy Carter was president and the Doobie Brothers released the #1 song “What a Fool Believes.” It was 1979. During the period of stagflation in the late 70s and early 80s, the economy had seen modest growth, and inflation had been ticking up for the better part of the decade. This can be traced to a stance of quantitative easing used by the Federal Reserve for the purpose of trying to reach full employment in the early 1970s. This eventually caused a wage-cost price spiral that exacerbated these mounting problems further. Around this same time, the U.S. dollar also lost its gold standard, which means it was a FIAT currency, causing a run on the U.S. dollar.

Turmoil surrounding the economic conditions of the U.S. started to worsen, but politicians were more focused on reelection and pressured the Federal Reserve to drop and keep overnight rates low. In the short term, this boosted the economy by reducing the cost of borrowing money, securing these politicians a little bit longer in office. But in the long term, they only lit the fuse on the time bomb of an ever-growing M2 money supply. Compound these factors with the Oil Crisis of 1979, which almost tripled the cost of a barrel of West Texas Intermediate crude.

As a result, inflation hit a peak of 13.54% year-over-year in 1980.

While the inflationary period of the late 1970s and early 1980s has some similarities to our current environment, there are also some stark differences.

- Past inflation drivers can be traced to easygoing and loose monetary policy, in which low levels of unemployment had been the goal. Similar to today, we saw an unprecedented time during the 2010s, in which rates were kept artificially low to create growth in the economy. Both of these policy stances saw a reduction in unemployment following a recession – the Great Recession in 2008 and the 1974 recession — but later contributed to a red-hot economy in which inflation thrives.

- The Oil Crisis of 1979 saw the price of oil nearly triple in a short span, while in late 2021, the war in Ukraine caused the price of oil to nearly double from a price of $65 a barrel to $123 by March 2022.

- As we all well know, the world was shut down by the 2020 global pandemic, which devastated many parts of the economy. The government intervened by pumping a ton of liquidity into the financial system and deferring debt payments. This new cash injected into the economy helped avoid a long-term recession… but came with the consequences of a sharp spike in M2. This was not the case leading up to 1979.

- We also saw major supply chain disruptions to the global economy during COVID. Factories abroad that sprung up in the 21st century were effectively shut down overnight, causing major supply and demand imbalances. Additionally, an incredibly strong labor market has prevented the U.S. from experiencing a so-called “hard-landing” associated with recession.

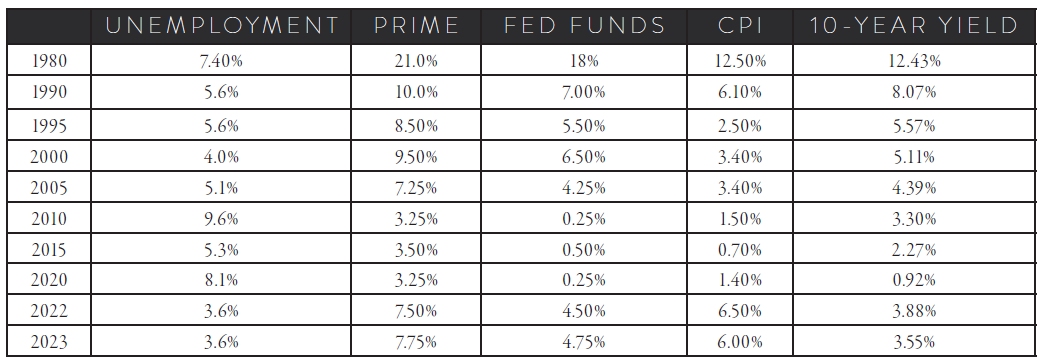

It took a particularly strong-handed Federal Reserve chairman, Paul Volcker, to finally get inflation under control in the late 1970s. Volcker aimed to follow the teaching of monetarist’s theories such as those proposed by famous economist Milton Friedman. Rather than target interest rates, Volcker chose to combat the ballooning M2 money supply. To do this, Volcker called a series of special meetings to raise the Federal Funds rate in correlation with the growth of M2, resulting in an effective Federal Funds rate in early 1981 of 19%. This would put the prime lending rate at around 21.5%. This crushed demand, and eventually led to a recession, but it was exactly what the U.S. economy needed after inflation had been raging for the better part of a decade. Volcker’s strategy was used as a blueprint for economic policy for the next four decades and allowed the United States to evade double-digit inflation through today – though we almost broke that mark in 2022.

THE IMPACT OF INFLATION ON COMMON AMERICAN CONSUMER GOODS

Our current Federal Reserve Chairman, Jerome Powell, has increased the Federal Funds Rate at the fastest clip in U.S. history.

Contemporary FOMC members have raised the effective Federal Funds rate by 4.75% in just a year, from a level of 0.08% in February 2022 to 4.83% in March 2023. While commodities

prices have fallen dramatically, the prices in services, food and shelter remain stubbornly elevated.

One final sticking point for the current administration is the robust labor market, which has remained at a 50-year low. Now the Fed is looking to reverse the trend of quantitative easing

that we saw in the 2010s, with the new narrative of “Higher Rates for Longer.” This, they hope, will get inflation more in line with the Fed’s 2% goal. Even so, the market is currently pricing in a significant cut in the Fed Funds rate by the end of the year, which directly clashes with this narrative.

_______

This content is part of our quarterly outlook and overview. For more of our perspective on this quarter’s economy, inflation, bonds, equities and allocation, read our entire 1st Quarter 2023 Macro & Market Perspectives.