Surprisingly, the 20th century unveiled some common economic trends between the United States and Midway through the century both countries had undergone a period of serious domestic turmoil, with The Great Chinese Famine occurring exactly 30 years after The Great Depression. Although both countries would eventually bounce back, there are fundamental differences in the decisions each country’s leaders took in order to recover. The impact on the economic decisions made in those crucial years can still be seen in our everyday lives, the largest being the ideological differences between the communist-based Chinese economic system and the capitalism-based U.S. economic system.

Though China is called a communist country, in taking a deeper look we see that the Chinese have an interesting hybrid economic model that uses both communist elements and capitalist ones. China promotes state ownership of key sectors while allowing private enterprise to operate in some areas. This pragmatic approach, initiated by reforms from the late 1970s under Deng Xiaoping, has fueled China’s rapid economic rise. The country has seen rapid ascendency from a largely agrarian society to the world’s second largest economy, thanks in part to being the number one exporter in the world. Despite this, the coexistence of market forces with stateled development has led to inefficiencies, structural challenges and even political turmoil.

While careful central planning from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has helped catapult the Chinese economy into a global superpower, that same planning is threatening to hinder growth or even disrupt key market systems. The Chinese government retains significant influence over key industries, such as banking, telecommunications, and energy, all of which are the most sensitive to regulation, censorship and supply chain disruptions. As a result, China’s strategy often stabilizes the economy in the short term but stifles competition and innovation over the long term.

Even with the information provided by the CCP, it is increasingly difficult to get an understanding of the true Chinese economy from an outsider’s perspective. We are often given misleading information (or no information at all) regarding the country’s economic conditions when communist leaders believe it may reflect poorly on the regime. A great example was in July 2023 – China posted their youth unemployment data at a staggering rate of 21.3% – and decided that they would rather suspend future releases of this report than face their economic situation.

Even more impactful is the Chinese government’s willingness to remove industry leaders and business owners in their country for speaking out against communist ideas or the CCP, undermining any consumer or investor confidence in Chinese companies. Many prominent CEOs have gone “missing” after denouncing practices by the central Chinese government. One high profile example of this is when Alibaba founder Jack Ma went missing in 2020, following a speech given at the annual People’s Bank of China financial markets

forum. Ma openly criticized China’s regulators and banks, after which he disappeared for over a year. Many suspected the Chinese government detained and “reeducated” the CEO during that time. This breach in open market practices and overall censorship has acted as a warning for potential startups and investors – the fickle Chinese government can – and will – intervene if they deem you an enemy.

THE HOUSING SECTOR

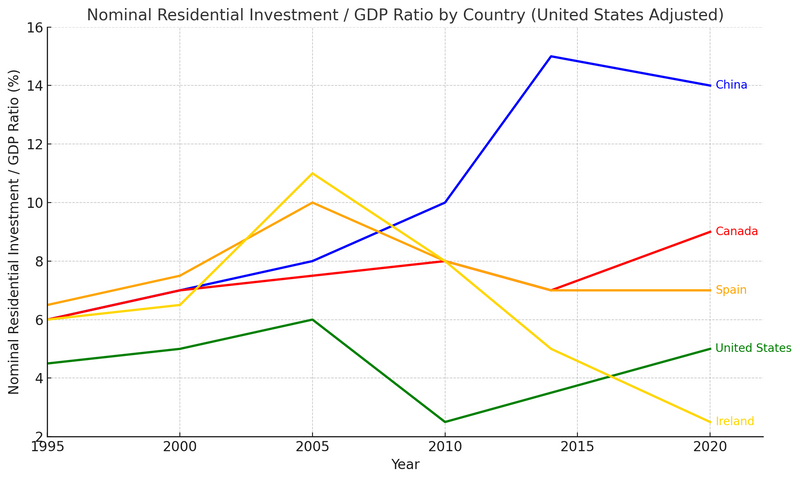

China’s housing sector, once a highpoint of their economic prosperity, has begun to show signs of deeply rooted problems. For years, China’s central planning authorities have encouraged rapid urbanization, leading to an enormous increase in new housing construction. Although this helped China with modernization efforts, it led to many speculative investments in the housing sector. As a result, Chinese real estate developers such as Evergrande began churning out as much new construction as possible, without a thought wasted on the proposition that the housing market might actually decline. With the building intensity came rising construction costs, which caused these developers to pile massive amounts of debt onto their balance sheets. As demand inevitably began to wane, these companies were suddenly left holding the bag. As time went on, many properties were left unsold and empty, creating “ghost towns” throughout the country. This culminated in early 2024, with the spectacular collapse of Chinese developer Evergrande. At the time of its demise, it owed around $300 billion to investors, with many of their future projects funded by pre-selling units to consumers. As a result, many investors and homeowners with money already invested in these projects were left without their deposit, their properties or their trust in the system.

LAND REVENUE SHORTFALL

Adding to the emerging crisis is another complication that ties in with China’s unique economic system – regional Chinese governments. Local Chinese governments have two main ways of creating revenue: selling usage rights to land under their government jurisdiction (as all land in China is owned by the government) and collecting land and property related taxes. By 2021, the share of revenue produced by land leasing had increased to 30% of total government revenue. This might have been a great idea when property prices were rising, but it introduced a host of problems when these values started to slip. Not only were they realizing less revenue from land leases, but vacant buildings and homes weren’t generating any taxes. All of this will eventually lead to less investment and spending by local governments. You can start to see how this cycle can perpetuate into an even worse slowdown, and why this raises alarms in Beijing.

RELIANCE ON LAND REVENUE DECLINES AMID DOWNTURN

HOUSING IS A HUGE ECONOMIC DRIVER IN CHINA

So, what has China done about this burgeoning economic disaster? It has released plans to create a stimulus program some journalists have dubbed an “economic bazooka”. The plan would introduce overall monetary easing policies throughout the country, in hopes of reducing debt and debt servicing costs for their largest developers as well as consumers. A few of the easing policies include:

- Lowering the Chinese banks’ reserve requirement ratio by 50 basis points

- requiring less cash on hand for major lending institutions

- cutting mortgage rates by 50 basis points to reduce debt servicing burdens on the consumer

- reducing the minimum down payment on new home purchases by 15%

- providing $71 billion to brokerage houses, mutual funds and insurance companies to buy Mainland-listed stocks through ETFs and large-cap stocks.

These changes might sound like a positive development for the Chinese economic system, but they actually reveal the seriousness of the underlying issues.

COMMODITIES

If China does have a 2008-like financial crisis, what does that mean for the U.S. consumer?

While it isn’t out of the realm of possibility, it is unlikely that a slowdown in China’s housing market would have a direct impact on Americans. However, we could see indirect effects on a global scale. One of the more interesting impacts of a Chinese slowdown would be commodities pricing – specifically, a large drop in demand and prices. With China being the world’s second-largest importer (following the United States), any decrease in demand would see huge implications for commodities like oil, natural gas, steel, copper and other precious metals. We have already seen a slowdown in demand for oil in China since the COVID-19 pandemic, putting downward pressure on crude oil prices.

This would impact the bottom line for many U.S. companies, which rely on the large consumer base in Southeast Asian countries (for example, Tesla or LVMH). Less disposable income for the average consumer means less to spend on non-essential goods. This is amplified when considering the Chinese population, now sitting at 1.41 billion.

Additionally, we could see a larger impact on countries with strong diplomatic ties to China. As China’s domestic struggles intensify, its ability to provide loans to developing nations may be compromised. China may even have to start calling on countries to repay existing debts, such as the whopping $26.6 billion total loan exposure to Pakistan.

China may have some significant economic headwinds in its future, but does that spell doom and gloom for the whole continent of Asia? Not exactly.

There are other nations in the region that are positioned for growth and could very well pick up some of the country’s global slack.

INDIA

One nation that the Investment Committee has taken a closer interest in is India. India and China share many of the same economic boons, including a large population, growing consumer base, and rapidly increasing living standards. India continues to attract foreign investments, particularly in technology and manufacturing. It has already seen a spike in economic growth over the past couple of years, with a tremendous recovery after COVID – one that China seemed to have missed – boasting a 9.7% annual GDP growth in 2021. It has continued to see high single-digit growth since. Unfortunately, it remains to be seen if India can take advantage of its momentum, as its increasingly bureaucratic government often gets in its own way.

China’s economic trajectory is at a critical juncture. While its state-controlled hybrid system propelled it to global prominence, mounting challenges remain in the housing sector, banking industry, and overall growth, raising questions about the sustainability of its economic model. As the Chinese government seeks to stabilize the situation with rate cuts and other interventions, the global implications are yet to be seen. From neighboring economies like India to major trading partners like the United States, China’s economic health has a profound impact on global markets.

IN SUMMARY

Despite the stark economic ideological differences between China and the United States, there are some striking similarities. From enduring hardships in the mid-20th century to potential housing market crises in the 21st, China appears to have adopted several strategies from the U.S. economic playbook. Ironically, one of those lessons seems to echo that of our 2008 financial crisis—an event China would have been wise to avoid.

This content is part of our quarterly outlook and overview. For more of our view on this quarter’s economic overview, inflation, bonds, equities and allocation read latest issue of Macro & Market Perspectives.

The opinions expressed within this report are those of the Investment Committee as of the date published. They are subject to change without notice, and do not necessarily reflect the views of Oakworth Capital Bank, its directors, shareholders or employees.