In 2024, particularly during the 3rd quarter, the only economic releases that have truly mattered relate to either labor markets or inflation. Everything else has been almost irrelevant. The ISM Report(s)on business? Big deal. Durable goods orders? No one is paying attention. Metrics like the trade deficit, monthly budget statement, regional purchasing managers’ indices, capacity utilization, industrial production, wholesale inventories, retail inventories, leading indicator sand a host of others? Okay Boomer. You do you.

The reason for this is simple. The Federal Reserve has a so-called “dual mandate.” These are price stability and full employment. To be sure, all of the releases listed above have some kind of correlation with those two things. However, why mess around with conjecture and mental gymnastics when the government is going to tell you exactly what it thinks inflation and job growth were the previous month?

Further, we know well in advance when they are going to do it.

- With perhaps an exception or two each year, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) releases “The Employment Report” on the first business Friday of each month.

- Also, the BLS typically releases the Consumer Price Index (CPI), the most widely cited inflation gauge, during the second full business week of the month.

- Of course, each and every business Thursday, the BLS reports on “weekly initial jobless” claims.

- If that weren’t enough, the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) releases the “Personal Income and Outlays” report on either the last business Friday or last business day of the month.

- This series contains the “price indices for personal consumption expenditures,” which everyone widely believes to be the Fed’s preferred inflation benchmarks.

If, for some reason, you just must have the specific dates, you can go to www.bls.gov.

Essentially, the investing public knows when the “real data” comes out, and is giving shorter shrift to pretty much everything else. Or so it would seem. If inflation and jobs are the two main concerns for the Federal Reserve, and Washington provides that information, then everything else is sort of just noise, right?

INFLATION & JOBS

When I got into the industry in the early 1990s, people still cared about the Federal budget deficit. Intuitively, this makes perfect sense.

- After all, the bigger the deficit, the more the Treasury must borrow in the financial markets.

- The more it borrows, the greater the supply of Treasury debt sloshing about the system.

- The greater the supply of debt, the more likely interest rates will go up.

Really, the thought process was good old supply and demand stuff. Basic economics.

Back then, no one would have dreamed the demand for debt would somehow swamp the deluge of it. However, times change, as do analysts’ preferred economic reports. Shoot, people used to seriously care about the Philadelphia Fed Report – a Business Outlook Survey that provides insight into the manufacturing sector – and it could move the markets. These days? Let’s just say the report’s popularity has declined.

This is important because the entire world has been waiting for the Fed to make a change to U.S. monetary policy for a very long time. More specifically, people have been eagerly awaiting a rate cut for nearly two years. However, inflation data continued to come in a little too high, and jobs numbers remained too strong. As a result, the Fed wasn’t able to cut the overnight lending target rate until the 3rd quarter.

INFLATION

First, everyone knows prices are higher than they were not so long ago. For many goods and services, they are much higher, as in eye-watering. In April 2022, the trailing 12-month CPI hit a 40-year high of 9.1%, and a lot of people thought even that number was too low. However, since that time, the rate of price increases has been increasing at a decreasing level.

As confusing as it may seem to the average consumer, that means the rate of inflation is coming down even if prices are not.

This has caused a disconnect between what the government says inflation is and what John Everyman’s wallet is telling them. How can Washington say inflation is coming down when a trip to the grocery costs an arm and a leg? Fair enough. But, as far as inflation is concerned, the powers that be focus on relatives and not absolutes.

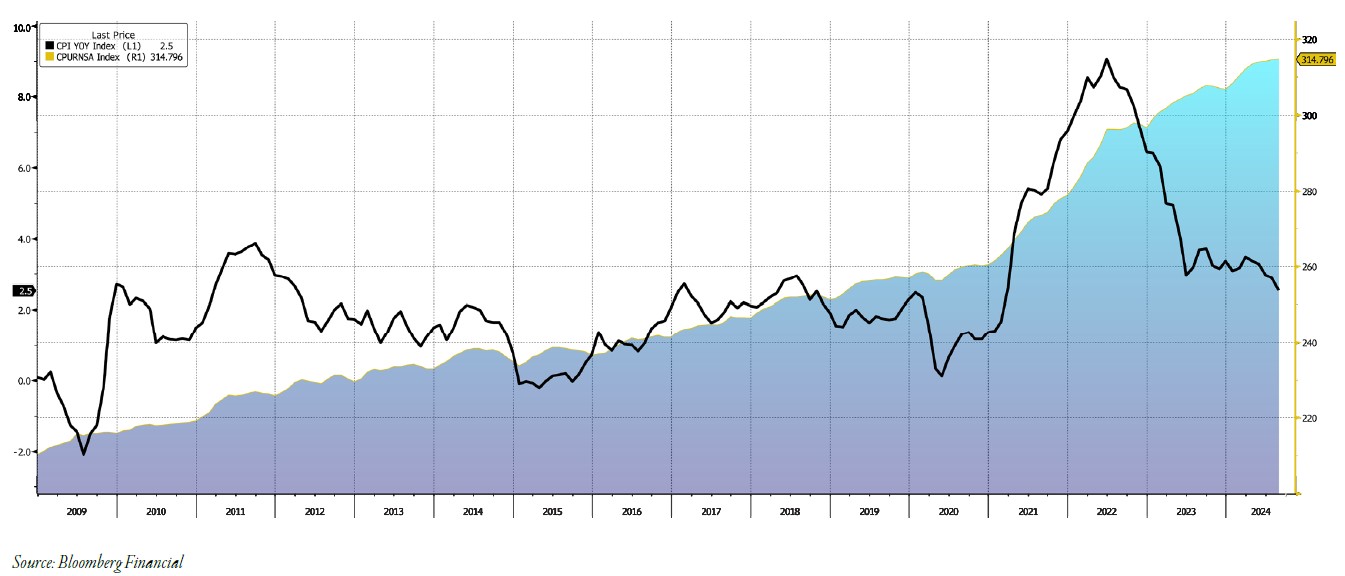

This is illustrated in the chart below. The dark black line represents how the 12-month CPI has come down while the shaded area, representing the aggregate level of prices, demonstrates how costs for the American consumer are still going up.

INFLATION IS GOING DOWN BUT PRICES ARE NOT

Fortunately, the Fed focuses on the black line instead of the shaded area. Obviously, it tells us inflation is coming down, which has given the monetary authorities enough reason to start making money cheaper in the U.S. economy.

As for your personal experience with inflation? Inflation has always been where you wanted to look for it, and everyone’s experience will be different. Personally, the official 12-month CPI for August 2024 at 2.5% probably doesn’t accurately reflect my household budget. However, that is the BLS’s story and they are sticking with it.

LABOR MARKETS

Then, there is the curious question about the health of the labor markets.

It’s well known that the job market was extremely tight when the economy reopened after the worst of the pandemic. Older people quit the workforce in droves, and it was hard to get people to work at any price, let alone one that made sense for employers. As a result, business owners added warm bodies as fast as they could, much like they did with their inventories. It didn’t matter if there was an immediate need for the headcount. They could worry about that later.

To that end, I would argue the tightness in the labor markets peaked during the middle of 2022. Since that time, things have started to slacken. The ISM Report(s) on Business have suggested as much.

The NFIB Small Business Hiring Plans Index would imply the same. So would just about every other economic report, except for the ones that matter.

As an anecdotal aside, my son graduated college this past spring, magna cum laude in finance. After he landed his first career-type job in March, I asked him how many of his fraternity pledge brothers had found employment. He said maybe 50% had, maybe. When I asked him about his friends who graduated in 2022, he told me 100% had either found a job or been accepted to graduate school by Christmas 2021.

Still, every month, The Employment Situation would report that the U.S. economy had created, or was creating, a head-scratching number of new, payroll jobs. It didn’t matter what business owners, my son, or other non-governmental economic data sets said. The labor markets were still on fire.

Until they weren’t.

LABOR DATA ADJUSTMENTS

This past quarter, in a move that surprised no one who analyzes the data, the BLS made a major revision to its previously reported data. By major, I mean it essentially erased 818K previously reported payroll jobs for the period from April 2023 to March 2024. That isn’t an insignificant number; this was on top of a previous monthly revision, almost all of them negative as well.

If that weren’t enough, it has wiped away over 200K jobs from its estimates for April through July 2024. In essence, over 1MM jobs that the BLS told us the economy had created didn’t really exist. Even more frustrating, it probably has even more revising to do to have the numbers jibe with all the other data.

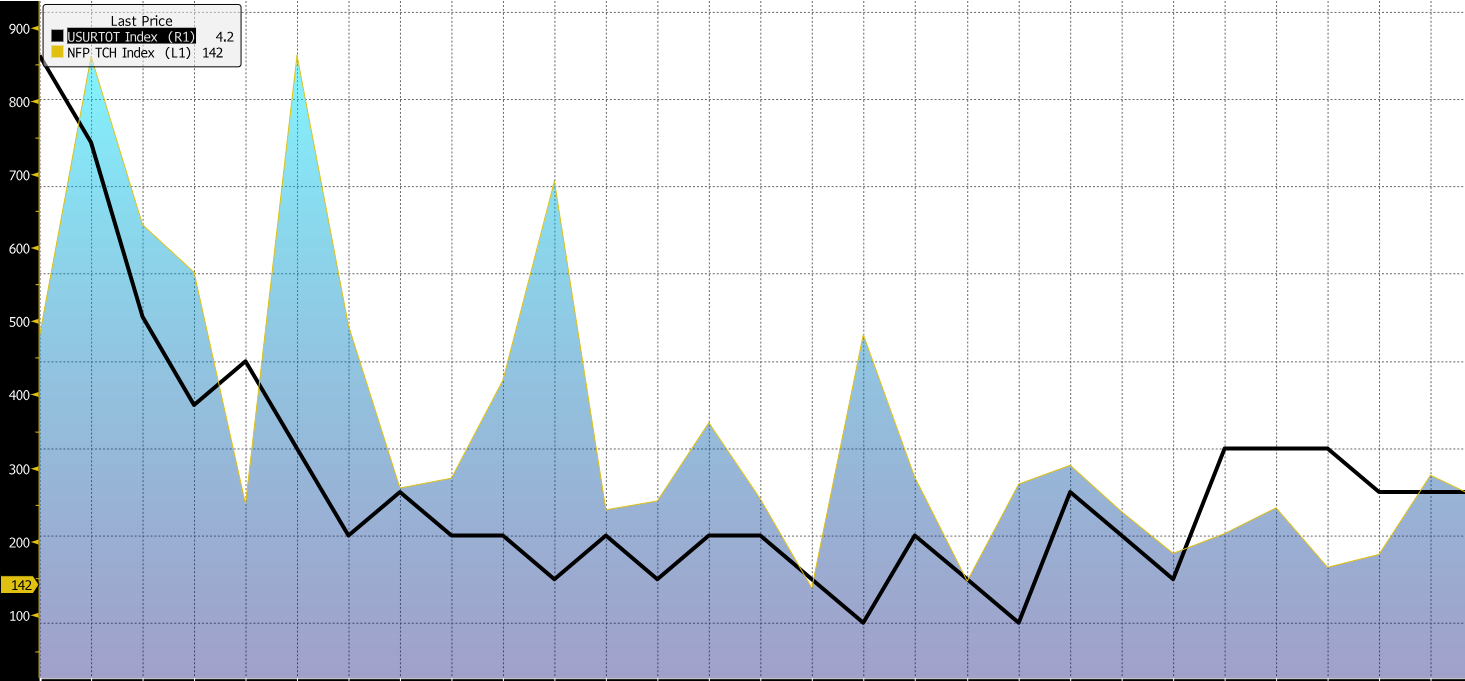

Even with all the changes, the monthly data had been suggesting the labor markets were cooling somewhat. Perhaps not as much as they actually were, but cooling nonetheless. Further, the official unemployment rate had ticked up ever so slightly to 4.2% from its recent low of 3.4% in January 2023. Is that 4.2% still too low? I think it probably is. However, as with the CPI, it is the BLS’ data, and what it says is what goes.

The dark black line in the chart below illustrates the rise in the official Unemployment Rate, while the shaded area demonstrates how monthly job gains have moderated.

FEWER NEW JOBS MEANS MORE UNEMPLOYMENT

How accurate are these numbers the government gives us? The answer is simple. No one should consider any of the data 100% accurate. It isn’t. It never has been. It never will be.

RATE CUTS

All of this came to a head during September. Price increases appeared to be under better control, even if prices were still too high. The labor markets seemed to be less overheated, even if the official data was still somewhat rosy. With these factors combined, the Federal Reserve finally had some room to cut the overnight lending target rate. After all, according to the reports that matter, the Fed had achieved some semblance of price stability and full, stable employment.

The question most people have, or arguably should have, is this: How accurate are these numbers the government gives us? When there seems to be such an enormous disconnect between them and what the average person is actually experiencing? The answer is simple. No one should consider any of the data 100% accurate. It isn’t. It never has been. It never will be.

No one really thought it was.

However, it wasn’t until this year, culminating during the 3rd quarter, that it became all too apparent that Washington needs to retool its methodologies to better reflect today’s economy and consumer behavior. The vagaries are simply too great and the implications too important.

Even so, and in the end, what really matters is the Fed finally embarked on its much-awaited easing cycle during the quarter. At the end of the quarter, the upper end of the overnight lending target range was 5.00%. By the middle of 2025, it will likely be somewhere in the mid-3% range.

If it isn’t, laughingly, the powers that be can revise their data sets to make it so.

This content is part of our quarterly outlook and overview. For more of our view on this quarter’s economic overview, inflation, bonds, equities and allocations, read the latest issue of Macro & Market Perspectives.

The opinions expressed within this report are those of the Investment Committee as of the date published. They are subject to change without notice, and do not necessarily reflect the views of Oakworth Capital Bank, its directors, shareholders or employees.