At the start of 2023, analysts and investors were very worried about the prospects for a recession. They also believed the Federal Reserve would start cutting the overnight lending target rate at some point during the year. Neither of these things happened.

Although these predictions were wrong, this past year was yet another confusing year for economic data. I suppose you could call it a post-pandemic hangover of some sort. Let’s hope it isn’t the so-called “new normal” The industry will have to learn a whole new set of correlations if it is, as a lot of the tried & true from the past no longer seems to work.

However, I have the luxury of writing this piece at the end of the year. During the 1st quarter of 2023, things were decidedly more uncertain than they are now. After all, a few nice-size bank collapses will tend to fray nerves and send people running for their bunkers.

In March, when the problems at Silicon Valley Bank (and others) became too great to ignore any longer, the risk of another financial system collapse seemed very real.

If these firms were failing because of the damage higher interest rates were causing to their balance sheets, why wouldn’t everyone else have experienced the same issues?

It is just math and Accounting 101. When rates go up, the value of the bond holdings on the asset side of the balance sheet falls. When this happens, assuming liabilities stay the same, the firm’s equity decreases. Obviously, if assets decline to the point where liabilities exceed them, the bank(s) could collapse.

Frankly, it didn’t take too much of a mental leap to imagine a domino effect of failing financial firms taking down the U.S. economy.

This, however, didn’t happen. Here’s why:

- Not all banks were as interest-rate-sensitive as the troubled ones were.

- The wobbly ones tended to have larger bond portfolios, which they had to “mark to market” as interest rates were rising.

So, what about banks that had a small amount of short-term bonds, say 10-15% of their assets? They were never in any real danger of failing. Conversely, those that had a large allocation to long-term bonds? Yes, they were in some trouble at the start of the year.

Fortunately, the worst-case scenario didn’t materialize.

The banking system didn’t fail. There wasn’t a repeat of the 2008-2009 Financial Crisis, at least not yet. But there were still other problems with which to contend.

THE MONEY SUPPLY

First, there is the decline in the money supply.

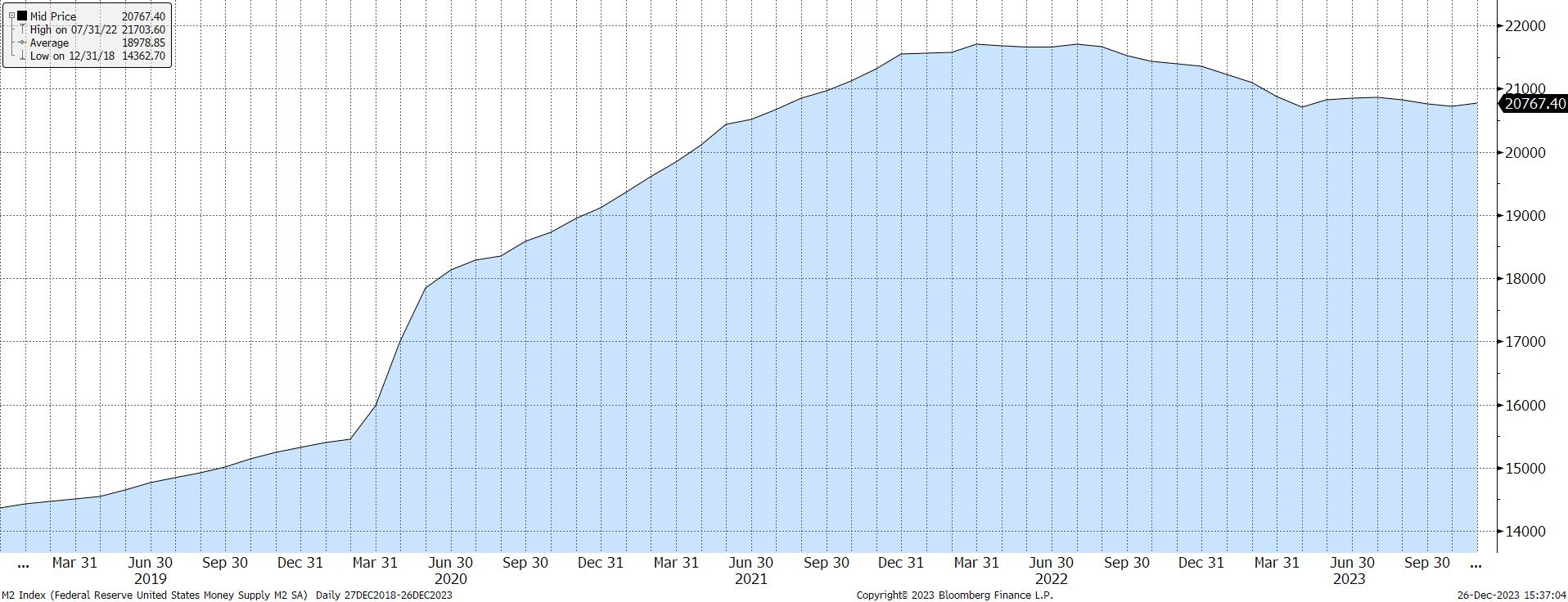

Intuitively, a decrease in the amount of money sloshing about in the economy isn’t conducive for growth. Further, it almost never happens. Surely, this would cause problems. After all, M2, the most commonly used supply gauge, fell almost a trillion dollars throughout the year, as is evidenced in the chart below:

GROWTH IN THE MONEY SUPPLY – OR LACK THEREOF

Going all the way back to 1959, there had never been a year-over-year decline in the money supply until 2022, when it fell 0.9%. However, at times in 2023, it got even worse. In April 2023, the trailing 12-month decrease in the amount of money in the system was 4.5%. By October, the last observation as of the time of this writing, it was 3.3%, or roughly $708 billion in absolute terms.

Surely, this would put a dent in activity, right? Apparently not, as the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) continued to report surprisingly decent quarterly Gross Domestic Product (GDP) numbers.

But how could this be?

Apologists pointed to the massive increase in M2 in 2020 and 2021 as the primary reason. While the supply of cash was indeed falling, it was doing so from artificially high levels thanks to Washington’s largesse during the pandemic and immediate aftermath. As such, there was, and still is, a lot of ‘excess’ liquidity sloshing about the financial system, more than enough to keep the economy’s wheels well oiled.

While that is an extremely logical explanation, and possibly very accurate, it still leaves a little head scratching for people who have been watching the markets for an extended period of time.

THE YIELD CURVE

Then there is the issue of the inverted yield curve. This is when short-term rates are higher than long-term ones. Thanks to the Federal Reserve’s attempts to quell inflation, short-term rates have skyrocketed over the last two years.

Since March 2022, the Fed has raised the overnight lending target a whopping 525 basis points (5.25%). This is the most aggressive it has been in doing so since the early 1980s.

Conversely, while they have gone up, longer-term rates haven’t increased by the same amount as short-term ones, either in absolute or relative terms. As a result, as of 12/22/2023, the yield to maturity on the 3-Month U.S. Treasury bill was 5.39%, whereas the yield on the 30-Year U.S. Bond was only 4.05%.

This is important.

You see, banks borrow short, in the form of deposits, and lend long. Typically, there is a nice, positive spread between what they pay and what they charge. However, if what banks have to pay depositors increases faster than what they can charge for loans, they make less money. As a result, they become pickier, if that is right word, about to whom they lend money, at what rate and for what length of time.

As was the case at times this past year.

“In other words, when the yield curve inverts, banks tend to slow down their extension of credit. When that happens, the money supply slows, or shrinks as it has recently, and economic activity cools. Sometimes, this is enough to send the economy into recession, but not always.”

LOAN GROWTH

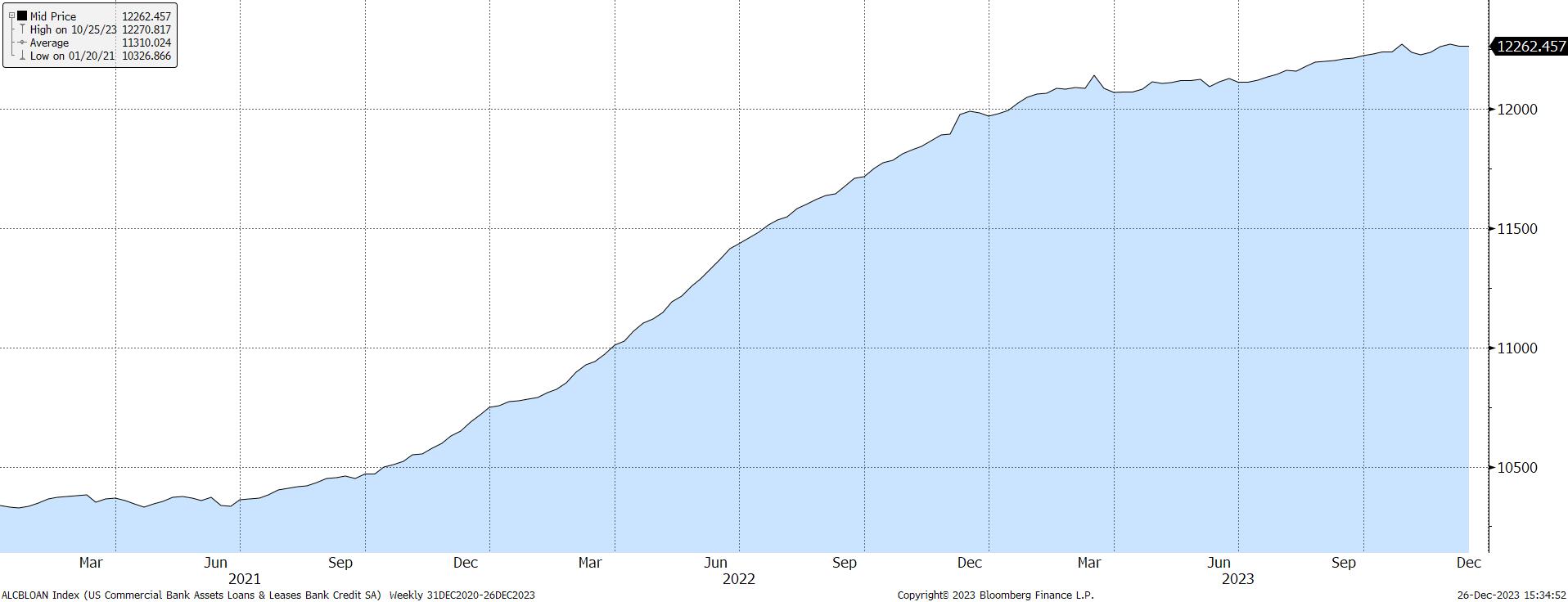

LOANS & LEASES IN BANK CREDIT

During the worst of the banking turmoil at the start of the year, loans and leases on bank balance sheets actually fell.

- After reaching a high of $12.139 trillion for the week ending on 3/15/2023, banks reined in their credit until the end of July.

- It wasn’t until the week ending on 07/26/2023 that loans and leases finally eclipsed where they had been in March.

That is a four-month stretch of not much happening in the banking industry. Trust me, this isn’t the norm. But, did it have a negative impact on the economy?

As you know by now, it didn’t, at least not officially. After all, the BEA reported the U.S. economy grew at a 2.1% annualized rate during the 2nd quarter of 2023. While there were some weaknesses in the report, it didn’t appear the quarter’s slowdown in loan creation was the problem it might have been in a simpler time.

- Bank failures? Check.

- A decrease in the money supply? Check.

- An inverted yield curve? Check.

- Stagnant loan growth? Check.

- Declining economic activity? Not so fast.

PURCHASING MANAGERS’ INDEX

If this isn’t, let’s call it, interesting enough, there is the case of the regional purchasing managers’ reports. These are surveys some of the regional offices of the Fed take to gauge economic activity in their area. Bluntly, the majority of them have been bad over the last 12 months, as in below zero, which would ordinarily portend contraction.

For example, the “Dallas Fed Manufacturing Outlook Level of General Business Activity” closed the year at (-9.3). While still bad, it was an improvement on the (-29.1) reading for May. Whew. If Texas isn’t growing, who is? Eerily similar, the “Philadelphia Fed Business Outlook Survey Diffusion Index General Conditions” was (-10.50) in December 2023, which seemed robust after the (-31.3) observation in April. Finally, the Kansas City Fed posted a (-1.0) number in November. Although that was much better than June’s (-12.0) data, it was a massive decline from the +32.0 reading in March 2022.

As such, it was safe to say a lot of the Federal Reserve’s regional information wasn’t exactly meshing with a lot of the official data. Most of the household and small business data wasn’t either.

HOUSEHOLD AND SMALL BUSINESS DATA

The University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment Index, a gauge of the average American’s thoughts about the current and future states of the economy, was 69.7 for December 2023. While that number might be Greek to many, the 30-year historical average, from 1993-2023, is 86.4. To be sure, it was higher this year than in 2022 when inflation was at its most crippling. However, it is safe to say the American consumer hasn’t been as ebullient as usual.

Neither have small businesses. To that end, the National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB) Small Business Optimism Index almost mirrors the University of Michigan data. The former’s reading for November 2023 was 90.6, which is a slight improvement from where it ended in 2022. However, the 30-year average for this series is 97.8, suggesting America’s small business owners don’t feel as confident as they would, could or should be.

So, with all of this negative news, how was it the economy’s GDP grew at 2.2%, 2.1% and 4.9% for the first 3 quarters of 2023, respectively? How was it actually able to accelerate so late in a Fed tightening cycle? From where is all of this strength coming? Especially when people were worried about a recession at the start of the year?

THE LABOR MARKETS

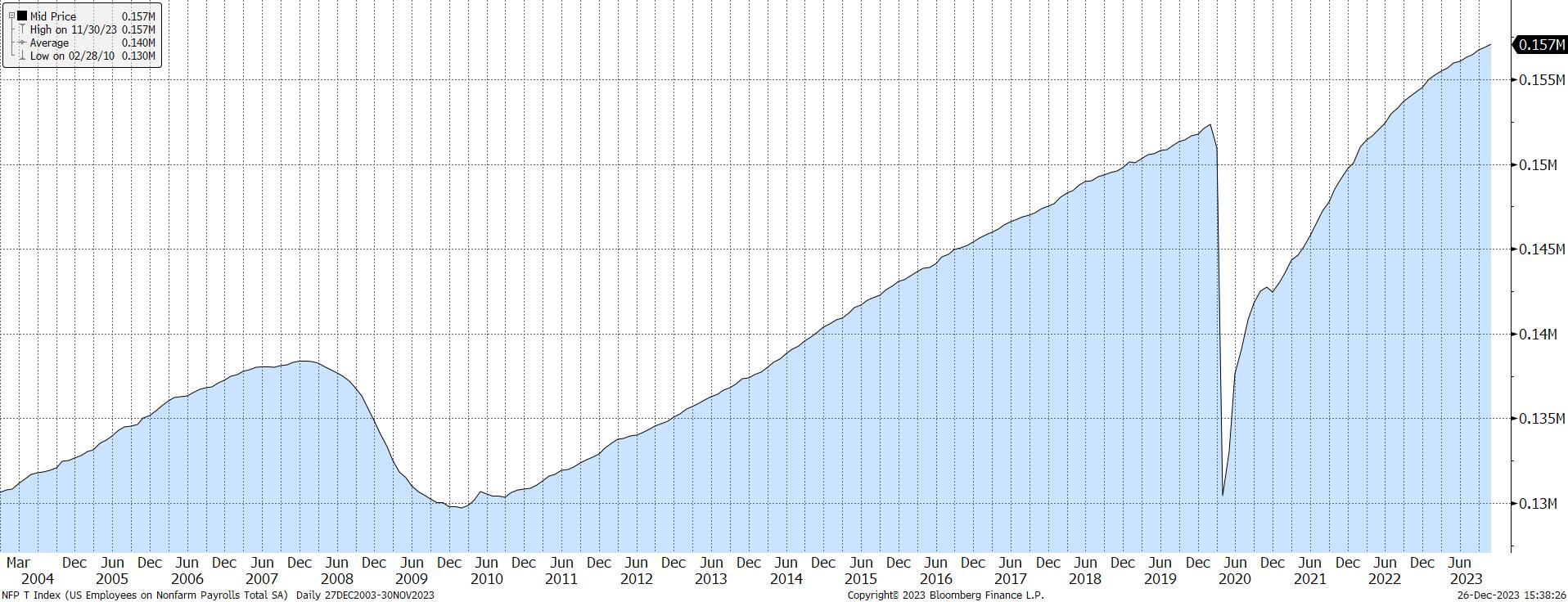

The easy answer to that question is the almost bizarre continued strength in the U.S. labor markets. They seem to have a life of their own. If not that, they are coated in Teflon.

Fed rate hikes can’t stop the jobs machine. Wars in Eastern Europe and the Middle East can’t either. Weak consumer and small business optimism? That isn’t a problem. Inverted yield curves, slowing credit creation, decreases in the money supply, and the heretofore unmentioned burgeoning Federal budget deficit are all so much child’s play.

U.S. employers are still having trouble finding enough capable workers to meet their desired capacity.

- The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported that the U.S. economy created 199,000 net, new payroll jobs during November 2023.

- For the 11 months ending in November 2023 employers added an impressive 2.81 million workers to their payrolls.

- The economy has now added back all of the jobs it lost during the pandemic plus about 4.4 million additional ones

As a result, the official Unemployment Rate was a miserly 3.7% this past November. Further, and perhaps more importantly, the Labor Force Participation Rate has increased to 62.8%, which is up sharply from the low of 60.1% it had reached in April 2020.

Basically, firms are hiring and folks are returning to the workforce.

TOTAL PAYROLL JOBS IN THE UNITED STATES

Employers are prone to be more reactive to economic conditions than proactive. So while the jobs numbers are arguably lagging economic indicators, their continued strength is providing a tailwind for the economy.

“Whether this tailwind will be strong enough to forestall any potential economic slowdown in 2024 is still anyone’s best guess. However, it will certainly mitigate its severity, perhaps significantly.”

The reason is simple. The U.S. consumer drives the U.S. economy. To that end, Personal Consumption Expenditures account for over two-thirds of the total GDP equation. As such, you can’t talk about the U.S. economy without talking about the U.S. consumer. Since paychecks are the primary source of income for the vast majority of U.S. households, you can’t talk about the U.S. consumer without talking about the job markets.

THE BOTTOM LINE

Essentially, when the economy is creating jobs, it is creating consumers. When it creates consumers, good things tend to happen in terms of economic activity. Such was the case in 2023. This continued (and somewhat surprising) strength in consumer spending spurred businesses to reinvest a little bit more in their companies and inventories than they would have otherwise.

That is, had the labor markets behaved the way one would have expected them to do so this past year.

How can 2024 possibly improve upon it?

In truth, it probably won’t, at least not at the first of the year. That isn’t to say the economy is going to falter. It shouldn’t. However, it probably won’t post another 4.9% quarterly observation, as it did in the 3rd quarter of 2023, for the foreseeable future.

“If you had to wager money on it, the easy bet would be to assume GDP won’t be as robust during the first two quarters of 2024 as it was the first two of 2023.”

It won’t be a bloodbath, but it should be a slowdown. The rates of inflation will continue to trend lower, even as prices remain high, and the employment picture will likely be a little softer than it has been.

All of it will be just enough for the Federal Reserve to start cutting the overnight lending target rate.

So, there you have it. In a lot of ways, we are ending 2023 similarly to how we ended 2022. A lot of folks are expecting a slowing in the economy, but not necessarily a recession. Further, virtually everyone believes the Fed will finally start cutting rates.

I suppose you can say everyone wasn’t wrong. They were just early.

This content is part of our quarterly outlook and overview. For more of our view on this quarter’s economic overview, inflation, bonds, equities and allocation read our entire Annual 2023 Macro & Market Perspectives.

The opinions expressed within this report are those of the Investment Committee as of the date published. They are subject to change without notice, and do not necessarily reflect the views of Oakworth Capital Bank, its directors, shareholders or employees.