Listen to the full podcast episode, here.

John Norris (00:30):

Well, hello again everybody. This is John Norris at Trading Perspectives. As always, we have our good friend, Sam Clement. Sam, say hello.

Sam Clement (00:35):

Hello John. How are you doing?

John Norris (00:36):

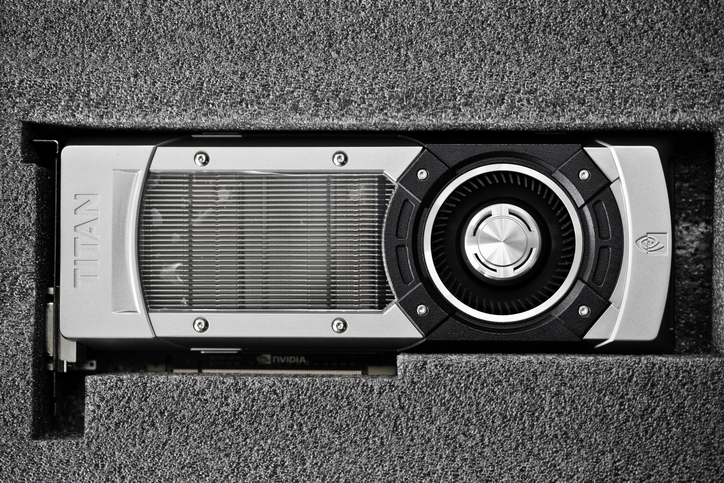

Sam, I’m doing okay and probably a lot better than the legal department over in NVIDIA.

Sam Clement (00:41):

You probably had a little wake up call yesterday.

John Norris (00:43):

Well, in case you just really don’t follow the business news or NVIDIA just in general. let me just tell you: The Department of Justice and all kinds of regulators around the world are just agag at NVIDIA’s rapid growth and their proprietary technology. And now we’re taking a look at perhaps antitrust against NVIDIA. And of course that’s going to send the markets reeling, send the stocks reeling because no one really knows what the regulators are going to find. And frankly, in a lot of ways it’s the regulator’s rules and they’re not necessarily real clear. And it’s kind of like you’re guilty until proven innocent.

Sam Clement (01:25):

Yeah, antitrust is kind of a buzzword in the business world and there hasn’t been as much actual companies being broken up, maybe Standard Oil, something of that sorts. But we’ve seen it with Microsoft lately going through a case. We’ve seen it with Google is always talked about because out of the big tech, they seem to have their tentacles in the most different lines of business. And Nvidia seems to be, you get that first that comes across the news. And they’ve been the talk of the town for what the better over a year at this point?

John Norris (02:01):

Yeah, probably 18 months now.

Sam Clement (02:03):

But AI has been the topic and NVIDIA is the biggest benefactor of that.

John Norris (02:07):

It is the poster trial for AI.

Sam Clement (02:09):

And so now it kind of seems just natural for the government to get involved in.

John Norris (02:16):

Well, it does seem sort of like deja vu all over again and talks about just bringing antitrust against some of the tech companies because if you’re a tech company and haven’t had the DOJ looking into what you’re doing, then maybe you’re just not all that good.

Sam Clement (02:29):

Yeah, you want to (laughs)!

John Norris (02:31):

Otherwise you haven’t been successful. But it really does kind of bring up a very valid point. Is Google having a near monopoly on the search engine business here in the United States, is that really a problem for consumers? Is Microsoft Word’s dominance in word processing – Is that really a problem for consumers? Is NVIDIA’s fastest chips ever and their ability to produce them just quickly and increase their technology each quarter, is that really a problem for consumers? And ultimately that’s kind of what the thought process is about breaking up some of these unicorns, the naturally occurring monopolies, if you will, is really what NVIDIA is doing bad for consumers.

Sam Clement (03:17):

And Microsoft was also a focus for video games.

John Norris (03:22):

Is that the problem for consumers?

Sam Clement (03:25):

And so the NVIDIA one seems, and again, it’s early. I mean we don’t really know the full scope of things, but if it’s a true, just focus on antitrust for what their business is, it seems a little unique compared to some past ones in the large tech space in that Microsoft has countless lines of business. Google has countless lines of business. NVIDIA is much more focused on sort of one line of business. It’s data centers and semiconductors, which are really not one in the same, but same industry.

John Norris (04:01):

They go hand and glove.

Sam Clement (04:02):

Yes. So that’s unique to this, but also there is lots of competition. What’s different about this too is there’s lots of companies competing, they’re just not as good. And that’s not my words. That’s the words of the CEOs that are justifying the tens and hundreds of billions of dollars they’re planning on spending.

John Norris (04:26):

Well, the reason why we’re going into all this today is because just to show that just because the government is doing something doesn’t mean it’s always a good idea for the consumer and frankly, Sam, in a lot of ways can do the consumer a lot of harm. So when you take a look at just kind of in history, breaking up monopolies, breaking up trust, I’m not exactly sure if there is a huge benefit necessarily for the consumers. John Rockefeller said when they broke up Standard Oil, “I’m wealthier now than I was” because he got ownership in all the breakups. And also what he said was, well, what did I do wrong except for make gasoline affordable to everyone and start off with kerosene. And when you take a look throughout history, when you have a naturally occurring monopoly, which is very rare, it’s generally because they’re producing a product that the consumer wants and they’re driving the price down in order to keep competition out. That is the whole of it.

Sam Clement (05:22):

That’s how it works.

John Norris (05:23):

Oftentimes the monopolies that we do have, frankly are created by the government and that’s when all of a sudden people don’t have a lot of choice. I mean, consumers don’t have any choice. Utilities are a perfect example of that.

Sam Clement (05:37):

Yeah, I always laugh about the marketing departments for different utility companies.

John Norris (05:42):

Why does Southern Company need to advertise in Birmingham? I mean Alabama Power is the power provider. In any event, kind of moving forward and taking a look at lawsuits or investigations by the DOJ and NVIDIA and what have you, it just kind of begs the question, just how involved do we really want the government to be in private industry… understanding that there are already a mountain of laws on the books about how governments, I mean how businesses should operate?

Sam Clement (06:14):

Well, the short answer is they’re too involved in my opinion. But I think with the keyword you talked about with some of these examples that we’ve discussed is the word “natural” in terms of how they came about because you kind of hit on it. To create a natural monopoly, you have to be offering a better product or service at a better price.

John Norris (06:36):

Generally somewhat unique.

Sam Clement (06:38):

There has to be these barriers for other companies to get in. I mean, talk about an Amazon being able to deliver something now in four to eight hours at a competitive price… that is really tough to build out and build the scale. That’s where the monopoly comes from in that sense.

John Norris (06:56):

And Amazon is working like the dickens to ensure that no one gets into that space, understanding that, hey, if they start jacking up their prices or what have you, people will just start going back to the store or they’ll go to walmart.com. They’ll do just about anything.

Sam Clement (07:12):

It’s like so many industries where there’s this kind of race to the bottom in terms of fees is one. And a lot of professional industries, whether it’s the cost of goods, what have you, you’re competing on getting prices down at scale. And so once you kind of achieve that, this all sounds largely good for the consumer. The problem is when you get those unnatural monopolies, and I think those are two completely separate issues.

John Norris (07:39):

I think the are two separate issues and not necessarily the issue I want to talk about here today. Because what I really do want to talk about is, again, government’s role in business. Understand that in a society you have to have someone to set the rules and someone to enforce the rules. It’s just the question of how involved you want the rule maker to be in how you conduct your lives and how you conduct business. And I would say that moving forward, we just can’t take anymore. I mean, when you take a look really at the size of the federal budget deficit at $35 trillion anticipated to add another 18 to $19 trillion over the next decade, we’ll easily, Sam, by the time you hit 40, have accumulated debt in the U.S. in excess of $50 trillion. The only sure way of reducing the government’s indebtedness, if not the outright level, but at least to decrease the increase in the annual deficit is to grow the economy.

(08:44):

That is a foolproof way in order to eventually increase tax revenue. It’s a perfect correlation. One to one. You grow the economy, there’s more money to tax, and there you have it. I mean, that’s just pretty straightforward. However, you don’t get there by putting regulations on business. And so that goes into sort of what the mindset is. If your worldview and mindset is: “we need to constrain business from making too much money and I’m cool with regulations,” that’s fine. Vote however you want, live your life however you want. However, if you’re looking at the world saying, “I want businesses and the economy to grow as rapidly as possible,” understanding that not everyone’s going to benefit equally, that’s your worldview. And so which one is best? Doing what I do for a living and how I was raised and how I view the world, I’d rather try to grow it as rapidly as possible hoping that I get some crumbs that fall off the table.

Sam Clement (09:44):

I think it reminds me of the saying that a rising tide lifts all boats and in that instance, they’re all risen equally, but we’ve seen this with countries that have massive economic expansion. It is the best way to increase the quality of life, the standard of living, decrease the poverty rate, what have you. All these metrics we have…

John Norris (10:08):

Is to grow your economy.

Sam Clement (10:08):

And it’s not about the government spending more if they had a little more change in their pockets then they could solve these issues. There’s already enough.

John Norris (10:18):

Yes.

Sam Clement (10:19):

I mean it’s so funny. We’ve talked about this, I mean years ago at this point, but these estimates for the cost to solve poverty, to solve homelessness, what have you, we have that money and we spend it on an almost daily basis. So this has never been a revenue issue.

John Norris (10:38):

Yes.

Sam Clement (10:40):

So …

John Norris (10:44):

I tell you what, next time you start preaching, turn around and face the congregation, my friend. I’m in the choir loft, and I’m going, yes, I love it. Amen, brother.

Sam Clement (10:53):

I love it. So the only way this works is growing the economy.

John Norris (10:57):

Yes, I think so. And I’ll tell you again, regulations are not there. And the reason why I say that is because when you have a regulation, there’s a cost of complying with that regulation. You have to ensure that that gets done. And it doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter how you want to phrase it, how you want to sell it to me. I will sit there and encounter every single time that whenever you put a new regulation, however small it is, that is an additional cost to doing business. That’s just plain and simple. I mean, by definition, a regulation is a cost of doing business because it prohibits you from doing something that you might do otherwise. And so if nothing else, you have the opportunity, forgone opportunity cost by having the regulation in place. Hopefully you would agree with me on that. So what happens when you have the code of federal regulation, which encapsulates all the regulations that we have on the books conducting a ton different things, Sam?

(11:54):

There’s 50 titles. 50 titles in the CFR, 200 volumes, 50 titles, 200 volumes, and over 200,000 page. 200,000 pages. It’s a lot. And when you think that the average Christian Bible has …not maybe your study Bibles, but your standard King James or something like that, depending on the font size, might be about 1500 pages. That’s the equivalent of 133 Bibles. Some people, I mean some people, it takes a full year of reading to finish the Bible if you start from the beginning to the end. So all that’s saying is you’re going to need 133 years starting now, Sam, reading every night to finish the current CFR.

Sam Clement (12:45):

I don’t like it.

John Norris (12:46):

So you tell me, Sam, I mean, you’re a young guy. You’ve got all the inside and new ways of doing things. I’m an old dog. You can’t teach me new tricks, no new tricks, anything like that. I sit, I sita lot and I beg a lot. Those are the new tricks I do. How can you sit there? How can anyone sit there and tell me that when we have federal regulations, this doesn’t include local ordinances or state laws, this is federal regulations, over 200,000 pages of rules and ways of doing business, all that stuff. How are you going to tell me that that does not have a significant cost for business?

Sam Clement (13:29):

It has to. And it’s more a quantifiable showing of the overall bloatedness of government in general.

John Norris (13:40):

But that’s not a Gen Z comment.You’re here for the Gen Z aspect of this.

Sam Clement (13:44):

I’ll have to think about what that comment would entail (laughs). But originally it was issues not expressly granted to the federal government.

John Norris (13:56):

But yet they’re granting it.

Sam Clement (13:57):

No, it’s everything. We’ve just completely thrown that part out the window.

John Norris (14:04):

And there is a cost to it, a severe cost to it. And this again really kind of leads me to, again, back to your worldview, is the role of taxation is the role of regulation to increase revenue for the government or to increase revenue for society? I am personally of the take that all this, everything the government should be trying to do would be to increase the size of the economy. Because let’s face it, if my slice of the economy is one eighth, so what? Right? It’s one eighth. Would you rather have a 15 inch pizza or a nine inch pizza?

Sam Clement (14:44):

Probably the bigger one.

John Norris (14:45):

Of course. Now, would I rather have a quarter slice, one quarter of a nine inch pizza or one eighth of a 15 inch pizza?

Sam Clement (14:54):

Yeah, you want the pizza to grow.

John Norris (14:56):

Yeah, I want the pizza to grow. So I mean, that’s kind of the way that I view this whole thing. And with the numbers that the government has given us, its estimates for the next 10 years, there’s absolutely no way I can fathom why, If you’re saying this is going to happen: another close to $20 trillion in accumulated debt, a growth rate of two and a quarter, two and a half, why is that acceptable? Why are we saying that’s acceptable? And I would say it’s not acceptable. And since I’m saying it’s not acceptable, the only way that we can make this somewhat palatable, lots of bigs word I think there is to grow the economy at 3% or more. And in order to do that, we need to unfetter the economy. I mean, let’s grow this bad boy. What are we doing? Why are we messing around? Why are we constraining companies? Why are we investigating NVIDIA? Why are we getting after Google just because it’s the dominant search engine.? Why are we doing this?

Sam Clement (16:01):

You sold me already.

John Norris (16:03):

It reminds me of a story that my father told me back when he was in graduate school at American University, getting his MBA. They had someone from the Kennedy administration a long time ago, long time ago.

(16:16):

Sixties. Yeah, early sixties. And the guy came in, I think it was Department of Agriculture, and believe it or not, back then, frozen, concentrated orange juice was still kind of relatively new. And the guy from the DOJ or the DOA, whatever he is USDA wherever he was from, came in and said, we’re going to get to the bottom of what they’re doing by God. We’re going to get to the bottom of the frozen concentrated orange juice business. And my dad remembered thinking, why? What’s there to get to the bottom of? They’re allowing everyone to have orange juice. We can store it better now. It’s not as perishable an item. And so that to me kind of summed it up. It’s good. This has been a long time coming, and it really does depend on where your worldview is. And I would tell everyone, listen, if you vote based on just good old fashioned social issues, none of this is going to change. None of what’s Sam and I are saying here today, it’s going to change your vote. Absolutely not. However, if your take is purely economic, by all means go out and read the policies and see which one is going to grow the economy far more rapidly. Now, the argument is that the Biden administration has done a pretty good job in growing the economy, at least the top line numbers. And that’s really been largely done, in my estimation, due to all this IRA money …

Sam Clement (17:45):

Government Expenditures,

John Norris (17:46):

Government expenditures, that while that has helped grow the economy, it’s helped to grow the budget deficit even more. And plus. So we can’t continue to have that type of growth for forever. We need to get back to letting businesses grow the economy as opposed to the other way around.

Sam Clement (18:03):

A war time or recessionary budget deficit is what we’re in right now with strong growth.

John Norris (18:09):

And so what would you like to see as Gen Z moving forward? What would be your ideal world in terms of the government’s involvement and how you live your life and conduct business? And what do you think we can really do about big bad business that is out to screw the U.S. consumer?

Sam Clement (18:29):

Look, I mean this is painting with a broad brush and there’s examples of monopolies that probably should be investigated and what have you,

John Norris (18:37):

But are those naturally occurring monopolies?

Sam Clement (18:39):

No, I, I’m envisioning companies that are paying off suppliers or what have you to gain illegal advantages and shut down competition.

John Norris (18:49):

I would argue there are already laws on the books like fraud and what have you, that’s already there.

Sam Clement (18:54):

The government loves repetitive laws and I could go into a lot of detail. I could go into a lot of detail on that. But we have more and more countries and international companies that are really trying to compete with us. And it seems like we are holding back. I mean, we are clearly holding back to an extent. So the only way we continue to maintain a competitive advantage is to allow the best companies on earth, which are in the United States, undoubtedly and arguably in the United States, to continue to be the best companies.

John Norris (19:29):

And the best way of doing that?

Sam Clement (19:31):

Let them do what they’re good at. I mean, the NVIDIA thing, and again, I haven’t read the full DOJ report, if it’s truly about the fact that they have the best product. I mean you can go back to 2005 in here, Jensen, their CEO, talking about things that are coming true right now with AI. He was a full step ahead of when the iPhone was coming out. He said, we’re going to move past the point where it’s click and a command comes back to you and starting to have this full AGI and this foresight that company had could possibly now be getting punished for 10 years of a headstart that really they took a risk on.

John Norris (20:10):

Well, and let’s say they do bust it up in some form or fashion, have to make that technology more widely available in the marketplace. Whats to stop our friends over in East Asia from getting greater access to it.

Sam Clement (20:26):

They’re already trying. And U.S. companies are trying. Semiconductors are not a one company industry. No, I mean there, there’s a handful based in the United States, large ones. Intel’s a large one, Micron’s a large one, Texas Instruments, AMD…

John Norris (20:44):

I guess Broadcom’s not technically and American company.

Sam Clement (20:46):

Not technically. So there is lots of available competition with laws already on the books about natural competition. And one company having the foresight to look into this and to invest in the future, decades before, literally over a decade before other companies were, is where they’re at now.

John Norris (21:10):

Alright, we are now kind of pushing up against our time limit. So I’m going to ask Sam kind of a loaded question. It’d be interesting to hear what he has to say about this. Now. We’ve talked a lot about NVIDIA and antitrust and tech companies and naturally occurring monopolies.

(21:29):

Do you think, and I don’t know if ironic is the right word, but paradoxical I think might be the best word, that the world’s largest monopoly, which is the U.S. federal government, is going after corporations that they view as monopolistic.

Sam Clement (21:49):

It is .

John Norris (21:51):

Hypocritical. I think

Sam Clement (21:52):

Hypocritical. I mean, this is an entity that has squashed competition. I mean, we could have a whole other podcast just listing out industries.

John Norris (22:05):

So when the federal government squashes out dissidents, people that are trying to break up its monopoly, that’s a good thing. But when the federal government, who tries to bust up monopolies itself, that’s also a good thing. Yeah, that’s two sides of the mouth.

Sam Clement (22:22):

It is.

John Norris (22:25):

Gosh. Oh man. Alright, well guys, we always love to hear from you. Also, if you feel so inclined, if you like what you’ve heard, by all means, drop us a line at or you can leave us a review on the podcast outlet of choice. Sam, I got to tell you, I really screwed that up to start with.

Sam Clement (22:44):

I don’t think so.

John Norris (22:45):

Well, okay. If you’re interested in reading more or hearing more of what we got to say or how we think, you can also go to O-A-K-W-O-R-T H.com. Take a look underneath the thought leadership tab for all kinds of exciting information, including links to previous Trading Perspectives, podcasts, links to our newsletter / blog Common Cents link to our quarterly analysis, which we call Macro and Market links to other articles from Oak Worth client advisors such as John Hensley, Richard Littrell, Janet Ball, and then as always links to articles from Mac Frasier and the remainder of the advisory services team. With that being said, Sam, come on again. Give me one more insightful thought on this exciting topic.

Sam Clement (23:26):

That’s all I’ve got.

John Norris (23:26):

That’s all I’ve got today too. Y’all take care.