This week, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), the policy making arm of the Federal Reserve, met, and didn’t make any substantive changes to current monetary policy. No one was expecting it to do so. However, it was a momentous meeting nonetheless, because the FOMC gave greater guidance about its future plans. Simply put, the Fed tried, and is trying, to telegraph its actions so there won’t be any surprises in the future. As we all know, the markets absolutely hate surprises.

As everyone who reads economic newsletters probably knows, the FOMC has kept its proverbial foot on the gas pedal since late last spring by flooding the financial system with liquidity and cheap money. Historically, this has been effective in mitigating any downturn in economic activity, and it has largely worked this time. However, as we all know, inflation has been rearing its ugly head, largely thanks to all of the money sloshing around.

Inquiring minds want to know just how much longer the Fed will ‘allow’ inflation to percolate. Through the end of the year? Next year? The year after that? How much more cash does it intend to throw at the economy? When does it all end, or does it?

For a long time, the markets have been operating under the belief the Fed intends to keep the gravy train going until 2023, at the least. Heck, Chairman Jay Powell has said as much. To be sure, some Fed officials, notably St. Louis President Jim Bullard, have been a little more hawkish in public. However, where the rubber meets the road, actions speak louder than words, and the Fed’s actions have suggested it is perfectly okay with inflation running faster than normal. After all, it is only transitory. Right?

But why would the central bank be willing to let this happen? Well, primarily because of the Fed has the ‘dual mandate’ of: 1) price stability, and; 2) maximum sustainable employment. As I type, the Fed hasn’t hit either goal, as the trailing 12-month Consumer Price Index (CPI) is currently 5.3%, and the official Unemployment Rate is 5.2%, as of August 2021. So, which one is it going to prioritize?

The answer to that question was in the meeting’s official statement. Here are the pertinent parts:

“The Committee seeks to achieve maximum employment and inflation at the rate of 2 percent over the longer run. With inflation having run persistently below this longer-run goal, the Committee will aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time so that inflation averages 2 percent over time and longer‑term inflation expectations remain well anchored at 2 percent.

The Committee decided to keep the target range for the federal funds rate at 0 to 1/4 percent and expects it will be appropriate to maintain this target range until labor market conditions have reached levels consistent with the Committee’s assessments of maximum employment…”

In the first paragraph, the Fed states its two goals and freely admits it will allow inflation to maintain “moderately above 2 percent for some time.” In the second paragraph, the Fed’s intentions are unambiguous: “and expects it will be appropriate to maintain this target range until labor market conditions have reached levels consistent with the Committee’s assessments of maximum employment.”

There you have it. When the labor markets strengthen significantly enough, the Fed will start tightening credit. So, what it that timeline? This is where it gets even more nerdy, and you are going to have to hang with me.

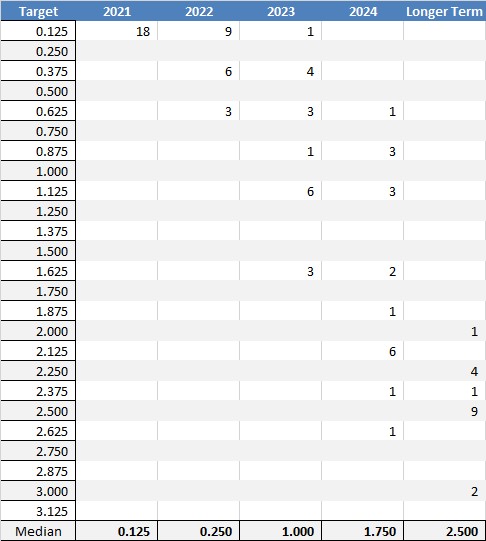

Along with the official statement, the FOMC released its ‘Summary of Economic Projections.’ Figure 2, on page 4, shows “FOMC participants’ assessments of appropriate monetary policy: Midpoint of target range or target level for the federal funds rate.” This is the so-called ‘dot plot chart.’ For simplicity’s sake, I took the information from the dot plots, and put them in an easier to read table (at least in my opinion). The numbers in the table are the number of respondents.

Let me help you read this a little bit. All 18 respondents believe the current range for the overnight lending target (0-.25%) is appropriate through the end of the year. Obviously, 0.125% is smack dab in the middle. By the end of 2022, 9 responded they believe the current range would still be appropriate, 6 stated a range of 0.25-0.50% would be ideal, and the remaining 3 forecasted a range of 0.50-0.75%. Taken together, the median estimate is 0.25%, which would imply a target range of 0.125-0.375%. Obviously, this would mean at least 1 tiny rate hike at some point next year.

Let me help you read this a little bit. All 18 respondents believe the current range for the overnight lending target (0-.25%) is appropriate through the end of the year. Obviously, 0.125% is smack dab in the middle. By the end of 2022, 9 responded they believe the current range would still be appropriate, 6 stated a range of 0.25-0.50% would be ideal, and the remaining 3 forecasted a range of 0.50-0.75%. Taken together, the median estimate is 0.25%, which would imply a target range of 0.125-0.375%. Obviously, this would mean at least 1 tiny rate hike at some point next year.

By the end of 2023, as you can see (after the little primer in the previous paragraph), the Fed anticipates it will be somewhat aggressive in raising the overnight lending target, as the median estimate spikes 0.75% to 1.00%. In 2024, the median rate increases to 1.75%, with the survey suggesting the overnight rate is most appropriate at 2.50% over the nebulous ‘longer term.’

So, there you have it. Instead of 2023, as we have been led to believe, the Fed could start to take its foot of the gas pedal as early as 2022. Since it is comfortable with a somewhat elevated CPI, this suggests the respondents in the survey believe the labor markets will continue to strengthen into next year. However, what is still unclear is: what is the committee’s definition of “maximum sustainable employment?”

Is it a miserly Unemployment Rate? Does it consider the Labor Force Participation Rate, which remains stubbornly low? Will it focus on the Establishment Data or the Household Data more? Will the Fed just be able to tell when things are strong enough, the old “it’ll know it when it sees it” approach?

I could be wrong, but I suspect it will probably be the latter.

So, what must happen? First and foremost, the economy has to start absorbing some of the massive number of available jobs. In July, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) announced there were an incredible 10.9 million job openings in July 2021. Interestingly enough, the Labor Force Participation Rate barely budged that month, and remains at the low (by historical standards) level of 61.7%. By comparison, it was 63.3% in February 2020, the month before things fell apart due to the pandemic. What’s more, it is the same level where it was in August 2020. As such, Americans simply aren’t going back to work…at least not officially.

That is going to change.

You see, up until Labor Day, many workers had a powerful incentive to not have a job due to pandemic related largesse out of Washington. Those unemployment benefits have now ended, and I suspect many of these people will begrudgingly start looking for work. Further, school is back in session, mostly in person, across the country. This means those adults, mostly mothers, which had to stay home to take care of children who couldn’t go to school, can start participating in the workforce again.

Don’t get me wrong, we likely won’t see a massive 1-month surge in job growth and participation. However, much will be in place for the labor markets to officially strengthen, perhaps sooner rather than later. To that end, I suspect an increasing number of Americans will participate in the workforce in the months to come, and there are 10.9 million jobs waiting for them.

If this does, in fact, occur, do NOT be surprised IF the Federal Reserve starts to reign in its incredibly loose monetary policy well before the end of 2022. No, it won’t go all Paul Volcker on the economy, or anything close to it. It will simply start taking its foot off the gas pedal, which will ultimately be a good thing for all of us.

Essentially, and in the end, that is what the FOMC told us this week, which made it a momentous meeting.

Take care, thank you for your continued support, and be sure to listen to our Trading Perspectives podcast.

Chief Economist

As always, nothing in this newsletter should be considered or otherwise construed as an offer to buy or sell investment services or securities of any type. Any individual action you might take from reading this newsletter is at your own risk. My opinion, as those of our investment committee, are subject to change without notice. Finally, the opinions expressed herein are not necessarily those of the reset of the associates and/or shareholders of Oakworth Capital Bank or the official position of the company itself.