This morning, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) announced the US economy created 559K net, new payroll jobs during May 2021. While this is a pretty gaudy number in absolute terms, it was still comfortably less than Wall Street’s 675K estimate. Further, while the Unemployment Rate fell from 6.1% to 5.8%, normally a good thing, the Labor Force Participation Rate (the percent of the working aged population participating in the workforce) inexplicably fell from 61.7% to 61.6%. I use the word inexplicably because there are an estimated 8.1 million job openings in the United States, easily an all-time high. With so many jobs to be had, why aren’t workers gobbling them up in greater numbers?

Great question.

This week, as is always the case the first full business week of every month, the Institute for Supply Management released its ‘Reports on Business’ for May 2021. These are some of my favorite economic releases, as I feel as though they are far less prone to, shall we say, manipulation from an invisible hand in Washington. In the May 2021 Manufacturing ISM Report on Business, here is “what respondents are saying,” and I am simply cutting & pasting from the report. The words are not mine:

- “Supplier performance — deliveries, quality, it’s all suffering. Demand is high, and we are struggling to find employees to help us keep up.” [Computer & Electronic Products]

- “Difficulty finding workers at the factory and warehouse level is not only impacting our production, but suppliers’ as well: Spot shortages and delays are common due to an inability to staff lines. Delays at the port continue to strain inventory levels.” [Food, Beverage & Tobacco Products]

- “[A] lack of qualified candidates to fill both open office and shop positions is having a negative impact on production throughput. Challenges mounting for meeting delivery dates to customers due to material and services shortages and protracted lead times. This situation does not look to improve until possibly the fourth quarter of 2021 or beyond.” [Fabricated Metal Products]

- “Labor shortages impacting internal and supplier production. Logistics performance is terrible.” [Electrical Equipment, Appliances & Components]

- “Business is good, but labor and raw materials are becoming very problematic, driving increases in costs.” [Furniture & Related Products]

- “Very busy, but still experiencing labor shortages.” [Primary Metals]

Now, consider these comments from respondents from the May 2021 Services ISM Report on Business, again I am simply cutting & pasting from the report:

- “Stimulus money, increased vaccinations, increased dining capacity and pent-up demand are driving a fast recovery for dine-in restaurants — and all consumer segments, it seems — resulting in labor shortages and supply chain gaps.” [Accommodation & Food Services]

- “(We are) seeing cost increases and long lead times with steel and steel containers. Worker shortages, temp labor and the like.” [Management of Companies & Support Services]

- “Small businesses in the area are reporting stimulus checks and extension of unemployment are hampering their ability to hire workers. Seasonal labor and H-2B (visa) workers are in very short supply, causing an uptick in cost per hour. Some employers are reporting they are offering cash incentives of (US)$50 if you show up for an interview.” [Professional, Scientific & Technical Services]

- “Business is very strong, and customer orders continue to increase at a rapid pace. Material shortages, increased prices and qualified personnel shortages are becoming a much larger concern.” [Real Estate, Rental & Leasing]

Taken together, it would seem corporate America is figuratively screaming it can’t find enough workers. How does that jibe with a still relatively high Unemployment Rate of 5.8%, an “underemployment rate” of 10.2%, and a stagnant (if not declining) Labor Force Participation Rate? As we might have said back when I was a kid: how now brown cow?

In real estate terms, you would call what is happening in the US workforce a “buyer’s market.” With generous unemployment benefits and somewhat desperate employers, workers can afford to be very choosy when looking for a job. I have seen it firsthand.

Without going into all the details, my son recently had a last-minute change in plans for the summer. No qualms on my end. However, this change resulted in him needing to find a way to, how should I put it, occupy his now more abundant time in a productive manner and help offset his social expenses. Since he has always had a good work ethic, this didn’t prove to be much of an issue, and it hasn’t.

Thus far, he has had at least two job offers he has turned down, with my full support. The first was at a local diner here in Birmingham, which basically told him to show up if he wanted the work and to tell his friends to show up too. However, the hours they needed, and the price they will willing to pay, didn’t realistically add up to enough to go to the trouble.

The second offer was from a public golf course outside of the Birmingham MSA, which was willing to give him as many hours as he wanted, at $7.25/hour plus whatever tips he could manage. Given the commute he would have to make, this didn’t make much sense, as just getting to and from work would gobble up almost two hours’ worth of pay. My wife and I gave him our blessing to turn this one down as well, largely because there seems to be no shortage of places looking for folks. In other words, he is being picky, and I can’t blame him for it.

Yeah, a lot of employers are looking for workers, a lot, but they aren’t willing to pay what has now become the new clearing price for labor. It is basic supply & demand, and, yes, the Federal government has skewed it with its largesse, to a point and with a certain class of worker. However, if my son’s experience is any indication, many employers are simply looking for workers from a workforce which no longer exists.

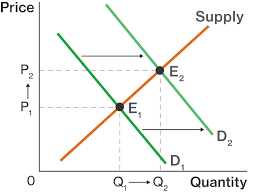

Consider the chart. It is nothing more than a supply and demand curve graph from an entry level Economics course. As you can see, the demand curve has shifted to the right (from D1 to D2), while supply (S1) has remained constant. What happens to price (P1 to P2)? That is right, it has gone up. Essentially, IF the demand for anything goes up faster than the supply, the price of whatever it is will go up.

Consider the chart. It is nothing more than a supply and demand curve graph from an entry level Economics course. As you can see, the demand curve has shifted to the right (from D1 to D2), while supply (S1) has remained constant. What happens to price (P1 to P2)? That is right, it has gone up. Essentially, IF the demand for anything goes up faster than the supply, the price of whatever it is will go up.

Of course, the Federal government paying people and extra $300/week to not work has impacted any supply curve shifts. However, the relatively sudden, historically strong surge in the demand for workers is undoubtedly greater than any corresponding shift in the supply of labor would have been even without the government programs. People, and workers, adapt to their current situation.

Going back to my son, last year he might have seriously considered taking that golf course job. He has done that type of work, bag attendant, for the last two summers, and enjoys it. Who wouldn’t? However, due to a gap in his, shall we say, social budget and our willingness to fund it this past school year, he now has some gig economy side hustles (which shall remain nameless). As a result, that minimum wage plus tips job on the course isn’t as attractive as it once was, nor is the job at the diner. True, he could probably make a little more at either actual job than his gig work, but it is nowhere near as flexible or convenient.

If this is playing out with my 19-year-old son here in central Alabama in his quest to find summer employment, you can imagine what is happening on a national level. The DoorDashers are still dashing, and getting their $300/week. The Lyfters are still giving people a lift. The folks at Shipt are still delivering the groceries. There are a few extra trucks with lawn mowers rolling through town. The list goes on and on, and, no they might not be making as much as they could be, but they are making enough, enough, to keep them from streaming back to their ‘old jobs’ at the ‘old pay.’

To be sure, we will see an increase in the Labor Force Participation Rate when the Federal government’s pandemic related, unemployment sweeteners expire. However, whether employers like it or not, they will likely have to pay more for what they previously had, in terms or labor, prior to the pandemic. Basically, the clearing price for labor has gone up for the near term. No, it might not be to Bernie Sanders’ desired $15/hour minimum wage for unskilled workers, but there is a reason why diners and gold courses aren’t getting people, like my son, to work for them: working 8 hours for $58 (total) isn’t really worth the effort for an increasingly large number of US workers. As my old friend in Baltimore, Stanley Martinez, might say: “they are seeing better away.”

Of course, any number of employers would, and will, tell me they can’t find workers at any price, and they might be telling the truth for what they realistically want to pay for a certain type of work. Historically, this has always led to greater use of technology and automation, to replace the workers who don’t want to work for what employers want to pay them. Then, and only then, will the price for labor go down, WHEN the demand for it decreases relative to the supply.

In the end, unskilled and semi-skilled US workers CAN be a little picky for a little while longer yet. However, the longer they are, the greater the likelihood they will become redundant. To that end, John has an interview this afternoon at 2:00, with a national firm. IF they give him a reasonable offer, my wife and I are going to insist he take it, even if he could cobble together more money delivering pizza or Chinese food. After all, the gig economy will always be there, but good jobs at good companies might not.

Take care, have a great weekend, and be sure to listen to our Trading Perspectives podcast.

John Norris

Chief Economist

As always, nothing in this newsletter should be considered or otherwise construed as an offer to buy or sell investment services or securities of any type. Any individual action you might take from reading this newsletter is at your own risk. My opinion, as those of our investment committee, are subject to change without notice. Finally, the opinions expressed herein are not necessarily those of the reset of the associates and/or shareholders of Oakworth Capital Bank or the official position of the company itself.