A couple of days ago, a relatively unassuming house in my neighborhood went on the market for a colossal amount of money. By unassuming, I mean an average-size 55-year-old rancher on about a half-acre of land. By colossal, I mean at a price slightly less than four times the last transaction in 2017.

While inventory in this area has been tighter than normal for some time, anyone looking to finance their purchase will likely have a hard time finding a local lender willing to do so. However, if recent history serves as a guide, it is very possible someone, or some firm, will pay for it with cash and be done with it.

As far as I am concerned, I hope they get their asking price – or even more – because it only works in my favor. That said, my first reaction was: “This has to be the top of the market.”

It very well could be.

As many know, the law of supply and demand ultimately determines the price of anything. It doesn’t matter if it is tiddlywinks or airplanes. If demand is greater than the supply available, the price will go up until there is equilibrium in the marketplace. Of course, the inverse is also true.

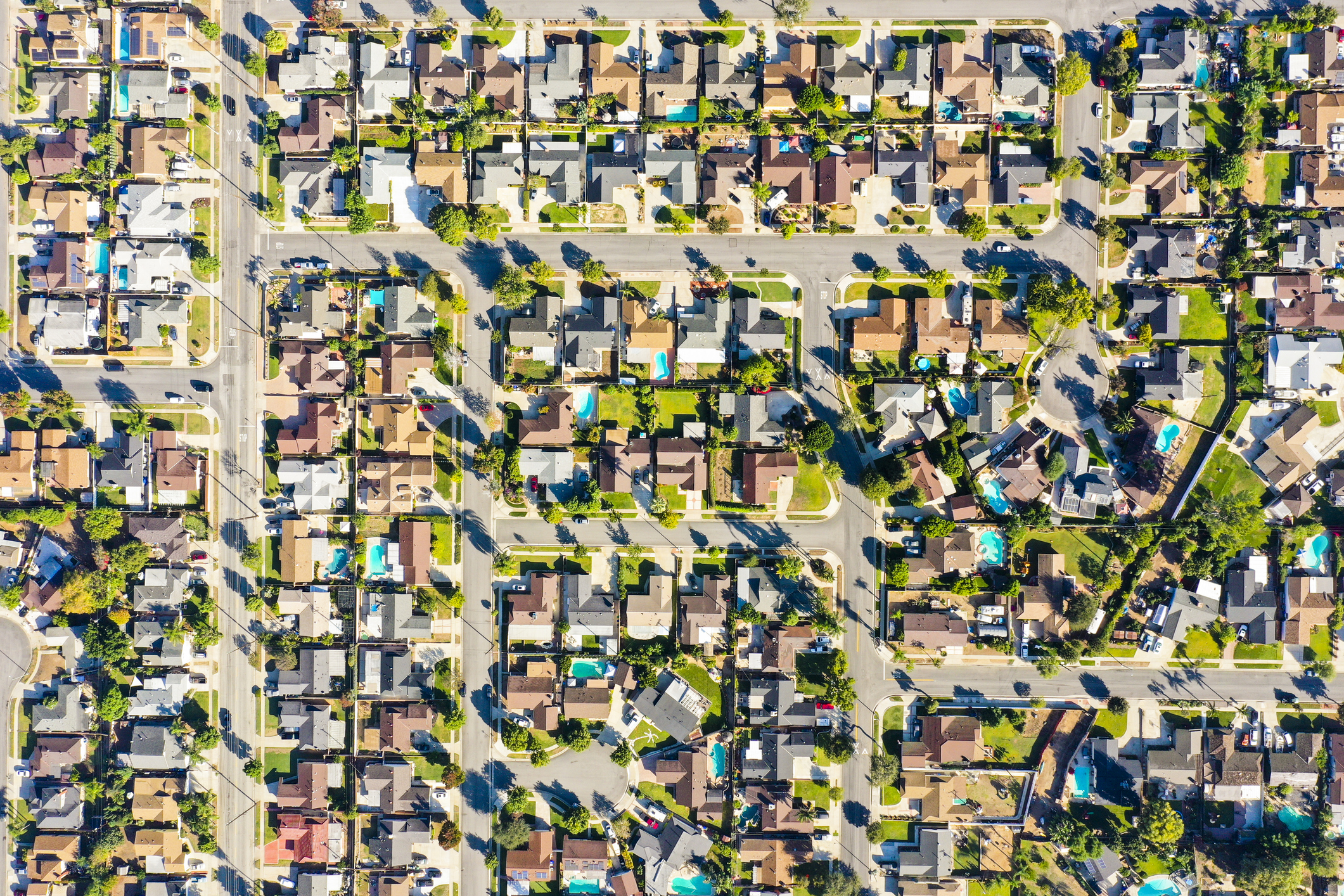

Over the past several years, housing prices in a lot of areas have gone though the roof. If basic economics hold true, this will mean the demand for housing has been greater than the supply.

To be sure, some would argue supply chain woes and a host of other issues have played a role in the eye-watering prices. No argument. But why have we had these problems? Again, demand has outstripped supply, even though higher mortgage prices would have suggested they shouldn’t.

After all, there wouldn’t be any supply chain issues if people weren’t demanding stuff, from ranges to sinks to countertops to workers. So, what will happen to the prices to these things, to housing in general, if demand were to slow?

Perhaps, counterintuitively, this could happen from the bottom and ultimately works its way to the top.

Over the past four years, the number of people immigrating to the United States, regardless of documentation, has been significant. Estimates are as high as being in excess of 8 million. No one will ever know for certain, almost by definition.

Obviously, all of these people need a roof over their heads.

So, what happens to housing prices, in general, when an unprecedented surge in immigration leads to greater demand? Demand greater than that which the housing sector anticipated? And what will happen to prices when the inflow of people into the country slows or even turns into an outflow?

In aggregate, prices should fall. Simple enough.

If fewer people are looking for Class C apartments, landlords will lower their rents in order to fill up their properties. Obviously, this will mean there will be an increase in supply of Class B units, and the owners there will also look to reduce prices. This, then, would create a little bit of a snowball effect.

To be sure, prices for homes on Eastover Road might not ever get the message. There are only so many of those houses and a lot of people want them. However, as immigration slows due to recent changes in policy, there is no way there won’t be a downward pressure on general housing prices starting at the bottom of the chain.

After all, according to most estimates, some 1.5-2.0 million people immigrated to the U.S. last year.* What if that number falls by, say, half? That’s roughly 1 million fewer folks looking for a place to put their heads at night. That isn’t an insignificant number.

This isn’t to say there is going to be a collapse in housing prices across the board. There likely won’t be. Demand in certain markets and sub-markets should continue to be strong. However, days of expecting to quadruple your investment after four years, like the folks selling that house in my neighborhood, are probably over for the time being.

In essence, the slowdown in immigration should serve as a pressure release value for the housing market. Again, this is in aggregate, as in across all property types and metropolitan areas.

Those under 30 reading this article are probably hoping I am right, and everyone over 50 feels quite the opposite. However, basic economics is ambivalent about age. It is simply how much is there and what is the demand for it?

With that said, I will be very interested to see where the final sale price lands for that house down the street from me.

Chief Economist

Please note, nothing in this article should be considered or otherwise construed as an offer to buy or sell investment services or securities of any type. Any individual action you might take from reading is at your own risk. My opinion, as well as those of our Investment Committee, is subject to change without notice. Finally, the opinions expressed herein are not necessarily those of the rest of the associates and/or shareholders of Oakworth Capital Bank or the official position of the company itself.

*According to Oakworth Capital Bank