Perhaps not surprisingly, I have gotten a lot of questions this week about what impact Donald Trump’s enormous wish list will have on the economy. More specifically, folks seem to be pretty worried about the impact his proposed tariffs will have on both economic activity and inflation.

It would seem intuitive that slapping large levies on foreign products would cause prices to increase. However, when you start peeling back the proverbial layers of the onion, it isn’t quite as simple as that.

Let me start by saying, historically, trade has been incredibly beneficial for economic growth. Please completely disregard anyone who would argue otherwise. The dissemination of goods, services, technology, information, ideas and, yes, money across vast distances and country borders has enabled us to enjoy the lifestyles we have today.

So, anything which would inhibit trade must surely be detrimental to economic activity.

Supply and Demand

With that in mind, all other things being equal, what might you assume would happen to consumer prices in the event of a slowdown in the economy? By definition, this would mean a decrease in demand. If what you learned in Econ 101 is true, when demand for anything falls faster than the supply of it, the price will decrease to a point where supply is equal to demand.

As such, should President Trump’s tariffs have a negative effect on overall economic output, consumer prices, in aggregate, would likely start to fall at some point. That is just what happens when people stop consuming stuff.

That should make some sense. But, won’t prices rise in the short-term before falling as demand decreases?

Everyone in the entire supply chain—from the firm sourcing raw materials to the retailer stocking the final product—operates with a target profit margin. They will do anything they can in order to meet it. However, someone, somewhere will have to absorb, say, a 25% tariff that Washington slaps on Product X.

Price Discovery

One thing is for certain. The consumer isn’t going to eat all of it, if much at all. The reason is more straightforward than you might imagine.

If consumers are willing to pay 25% more for a product/service, they would already be doing so. The marketplace would have sniffed that out long before the imposition of a tariff. You can call it “price discovery.”

To be sure, a consumer might occasionally cough up more than they would like for something. Anyone who has eaten at an airport knows that. However, would you honestly consume as much of, we’ll call it, Breakfast Biscuit X if the airport price was the prevailing market price? More than likely not.

So, are you willing to pay significantly more for [name your product] because of a tariff? Do you no longer have a say in the transaction? Would you just have to take whatever price they ask? Are there no alternatives? Everything is inelastic and you have to buy it regardless of price?

Of course not.

In a consumer-driven economy such as ours, we ultimately have the last word when it comes to price. It might not always feel that way. However, absent what is almost always a government-protected monopoly, there is precious little “take it or leave it” price setting in the real world.

Then, there is a more monetarist approach.

If we HAVE to spend significantly more money on Product Y because of tariffs, we will have less to spend on Product Z. As such, the makers of X have a decision to make: should they keep producing the same amount and accept a lower price for it? Or should they cut back on supply to maintain price stability?

If they continue to produce at the same level and accept a lower price, this will mitigate the inflationary pressure from the tariff. If they decide to produce less, this will reduce the demand for all of the inputs necessary to make X. As a result, prices for those inputs fall, which will have a ripple effect across the economy.

Essentially, unless there is a commensurate increase in the money supply, businesses cannot pass along all of their cost increases to the end consumer. If they could, companies would never go out of business or layoff employees. Obviously, those things happen all of the time.

Inflation

You see, at the end of the day, inflation has two primary causes:

- When consumer demand is greater than the level of supply, and/or;

- The monetary authorities artificially increase the money supply, thereby decreasing its value.

Absent those two things, competition in the marketplace and consumer reticence will largely counterbalance exogenous price increases.

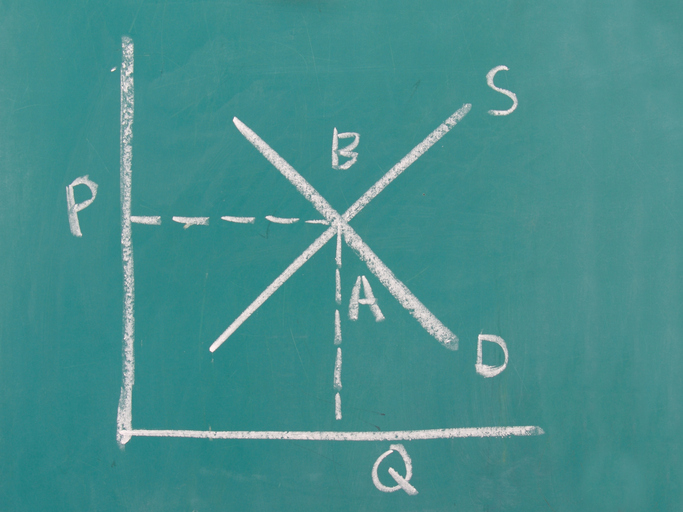

Therefore, inflation isn’t the biggest long-term problem stemming from tariffs. A slowdown in economic activity is due to decreased demand across the supply chain. No? Go back and take a look at an old-fashioned supply/demand curve graph. Simply increase the price along the Y-axis, and tell me where the new “point” is on the demand curve.

That is Geekspeak for “when the price of anything goes up, the demand for it goes down.” Hey, President Trump might be a lot of things, but immune from basic economics isn’t one of them.

Tariffs

So, in the end, are tariffs tarrible or tariffic?

After mulling this over, if I had to choose one over the other, I would have to say tariffs are tarrible. Frankly, I can’t come up with any scenarios where they are tarrific across the board. However, that is if I had to choose one over the other.

The best answer to the question is “tariffs lean more to the terrible than the terrific. While they might cause significant pain in select industries, their impact on the entire economy likely won’t be anywhere close to the nightmare scenario many are fearing. The economy won’t fall through the floor and inflation isn’t going to bust through the ceiling.”

There, I have said it. NOW, moving forward, I will know who hasn’t been reading Common Cents when they ask me about tariffs and inflation!!!

Thank you for your continued support. As always, I hope this newsletter finds you and your family well. May your blessings outweigh your sorrows on this and every day. Also, please be sure to tune into our podcast, Trading Perspectives, which is available on every platform.

John Norris

Chief Economist

Please note, nothing in this newsletter should be considered or otherwise construed as an offer to buy or sell investment services or securities of any type. Any individual action you might take from reading this newsletter is at your own risk. My opinion, as well as those of our Investment Committee, is subject to change without notice. Finally, the opinions expressed herein are not necessarily those of the rest of the associates and/or shareholders of Oakworth Capital Bank or the official position of the company itself.