2021’s most inescapable cocktail party conversation may not actually be around a virus and its mutations, at least in some circles. Instead, this year’s winner may be our very own Central Bank’s decisions in regards to the implementation of monetary policy.

Enacting appropriate monetary policy is job number one for the Federal Reserve, so, by default, the Federal Reserve’s primary responsibility is control over the country’s supply of money. Obviously, because of this, when there’s talk of a potential rate hike, in turn tightening available cash ‘in the system’, folks start to pay a lot more attention to the Central Bank’s outlined policy.

As luck should have it, pandemic-induced stimulus provided significant liquidity in a near-zero rate environment, flushing the monetary system with cash. Now, as a robust economic recovery continues to unfold, central bankers must take a hard look at the policies they previously put to work, and ultimately debate the timing of a rate hike.

First and foremost, the phrase ‘the Fed’s raising interest rates’ is a bit deceiving. In reality, the Fed doesn’t directly ‘raise’ interest rates. The Central Bank raises the fed funds rate (aka the federal funds target rate) which serves as a reference, or baseline, for the interest rates commercial banks charge for overnight lending in order to meet the required liquidity set by the government. Current credit conditions can impact the latter, but we’ll not fall too deep in that rabbit hole and just leave it at that. So, due to a bit of an indirect arrangement, the fed funds rate has become the most important benchmark for interest rates, within the U.S. at least, and it can influence interest rates globally.

Well, what happens when the Fed raises rates? That is the trillion-dollar question. Fed fund rates would be raised in order to increase the costliness of credit throughout the economy as a whole. By having higher interest rates, loans become more expensive for both the individual consumer and businesses as everyone inevitably pays more interest on their payments. This increase in the cost, or the ‘price’ of money, can discourage folks from engaging in projects that may require financing at some level. Simultaneously, it encourages folks to save more money to earn additional capital in order to make these higher interest payments. Because of this, the supply of money in circulation is reduced. This is nothing too complex – saving more equates to spending less which allows for fewer greenbacks to float around various pockets. A reduction in the supply of money can ameliorate hotter-than-desired, or anticipated, inflation (sound familiar?) and can moderate economic activity. This ‘cools off’ the economy – which is not always a bad thing.

Not always a bad thing? But wait, don’t we want economic activity running red hot? Not necessarily, at least not all of the time. The Federal Reserve has two primary jobs: 1) to ensure price stability 2) to ensure an appropriate employment rate. As the U.S. economy continues to ‘run hot’, or as the recovery continues to unfold with greater velocity than what was once expected, the Fed must still abide by these responsibilities. Because of this, a rate hike ultimately evolves into the inevitable outcome, particularly when dealing with such low rates initially, to ensure continued growth and stability – and not a transitory spike. If not, the economy may face a period of stagflation similar to that of the 1970s simply due to the sheer amount of dry powder previously injected into the system. A rate hike will not necessarily derail the continued strength behind an economic recovery, but rather it will try to extend the recovery while ensuring appropriate price and job stability.

In short, a rate hike essentially boils down to a tool the Fed may utilize to complete their balancing act of keeping both employment and prices in their appropriate ‘lanes’ without whipsawing a dramatic effect to one side or the other. Along these same lines, a rate hike provides flexibility, or leeway, for the Federal reserve to continue its balancing act. If the economy was to incur a speedbump of sorts, a higher Fed fund target rate would allow for flexibility in then cutting rates, easing monetary policy, and allowing for the economy to have a more accommodative environment to stabilize.

Okay – enough with the brain games. Let’s see what this looks like. If the Federal Reserve was to increase the target rate by 1.0% (no, the Fed’s next rate hike will not be this but let’s pretend), how might that effect a mortgage loan? A $300,000 30-year mortgage loan at 3.5% would carry about $185,000 in interest of its lifetime. This makes the monthly payment a bit more than $1,340. If the Fed was to raise their target rate by 1.0%, this same home mortgage would carry about $247,000 in interest over its lifetime. This translates to nearly $1,520 a month – a $180, or over 13.4%, increase in each monthly payment. As we have all experienced in some capacity through our lives, those ‘extra’ dollars add up fast, and they can have a lasting impact on a family’s decision(s).

In this specific example, a family may attempt to mitigate the increase in expense through the delay of a purchase of a home, or they may opt for a cheaper or smaller mortgage to try and offset some of their monthly payment. This can lead to a shift in the attractiveness of saving relative to spending. Homes ultimately could become less attractive, particularly when there has been a run-up in home prices ahead of a rate hike like we are currently seeing, as debt-servicing becomes more expensive. These changes in decision making (purchase patterns) can fundamentally shift the demand different markets experience before and after a rate change.

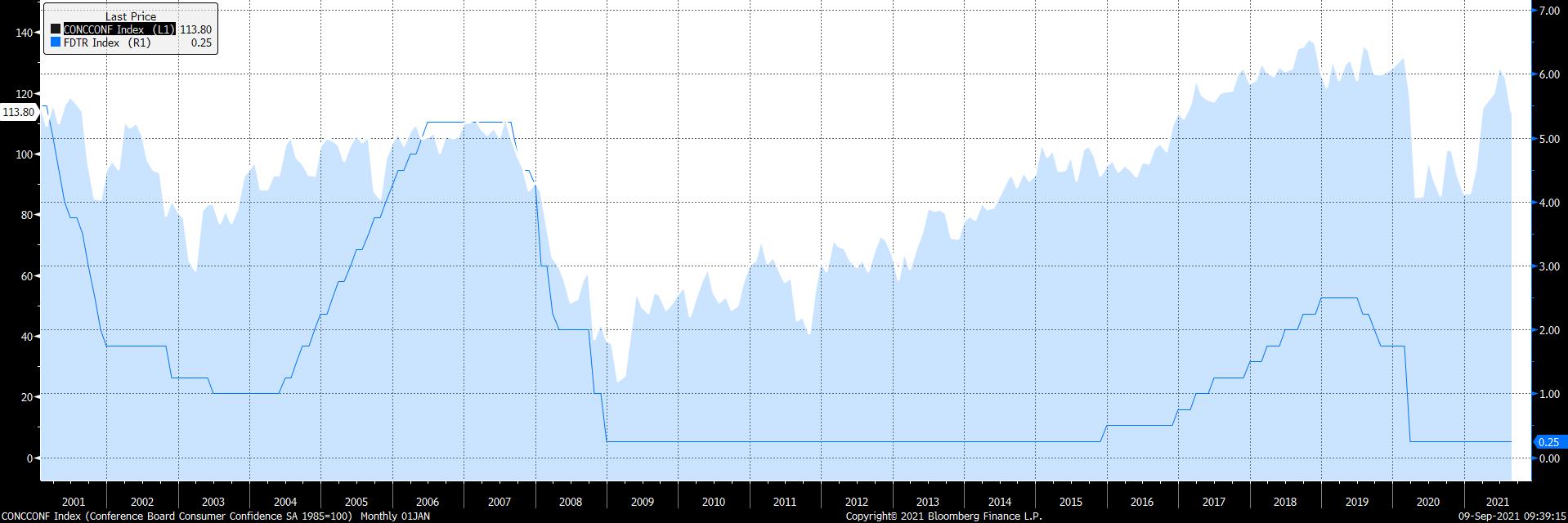

Conference Board’s Consumer Confidence Index’ plotted against the ‘Fed Fund Upper Target Rate over the past 20 years

Let’s back up for a minute, though. Earlier, we discussed rising rates increasing the cost of borrowing. This increase in cost inversely shares a relationship with disposable income as the latter decreases. A decrease in disposable income limits growth in consumer spending. This same increase of cost also limits consumer investment – the two travel hand-in-hand. Thus, the combination of a limitation, or decrease, in both consumer spending and consumer investment leads to a fall in aggregate demand. Here lies the ‘real’ reason an economy will cool in periods of rising rates.

In addition to this, a rising rate environment can lead to currency appreciation. The value of a/each dollar shares a direct relationship with interest rates, the two moving in tandem. So, with global trade in mind, exports from a nation experiencing rising rates become more expensive (less competitive) and imports become less expensive (more competitive). This shift in preference towards cheaper imports can and will lead to a larger trade balance – the difference between exports and imports. While the United States’ monthly trade balance report has waned in significance over the course of the past several decades, the lasting effects of this shift touches essentially every industry.

Over the course of the past 18-months of a global pandemic, we have been allowed a firsthand look into a now all-too-familiar event – corporate cost-cutting. During periods of rising rates, where there is downward pressure on excess liquidity, cost-cutting remains prevalent. As expenses increase with interest rates, business owners may feel the brunt of this on their bottom lines and be forced to rely more heavily on alternative methods of overhead. If the past year and a half served as any indication, an increase in the reliance on technology can greatly mitigate the costliness of overhead. As a result of this, not only could unemployment see a spike due to the increase in the cost of debt-servicing, but technology could see even greater adaptation in the workplace – particularly in regards to the replacement of warm bodies in seats.

So, what now? How do we best prepare? First, it should be noted that not all Fed hikes will be felt directly by every consumer. Additionally, and perhaps more importantly, not every corner of your financial life will even be affected by rate changes. In fact, there a very good chance that when this first rate hike occurs, the average American will not notice anything different; however, keeping tabs on the Central Bank and its policy shifts should remain an important part of everyone’s financial wellbeing. As we have previously covered in this series, one of the best methods to mitigate any impact(s) of rising rates is to strike the best allocation of stocks/bonds/cash in your portfolio, and this is a conversation Oakworth Capital’s Investment Committee has with the utmost regularity.