Through dumb luck and sheer happenstance some 30 years ago, I found myself working at a buy-side, bond trading desk in Baltimore. To say I didn’t really know what I was doing would be an understatement, but my bosses at the time apparently saw some potential in me. Either that or I was already within the organization, Mercantile-Safe Deposit & Trust Company, and I was willing to work pretty cheaply. Perhaps it was a combination of those things.

While I had some general, business school knowledge about bonds and how they work, I didn’t have any practical experience with them. I knew they paid a periodic rate of interest and matured at some point in the future. I also understood their value moved inversely with the direction of interest rates. This means when interest rates go up, bonds prices go down, and vice versa. Easy peasy, nice and easy.

Over the years, I have learned more about bonds than I ever thought I would. As my individual understanding has increased, I have realized something: most people don’t know that much about them and care even less. They find the bond market safe, predictable, and, well, boring.

This is primarily due to the fact interest rates have largely been falling over the last several decades, meaning bonds have been going up in price. Further, up until 2008 or so, they paid a comfortable rate of interest relative to inflation. After all, what’s not to like about, say, a 2-Year US Treasury Note yielding 4.75% when inflation (CPI) is running at a 3.1%, as they both were on 12/31/1991? That is a pretty decent return in both absolute and relative terms, and it was oh so simple.

As a point of clarification, most other types of fixed income securities (bonds) price ‘off’ the US Treasury with the most comparable maturity. For instance, a bond trader might quote a 2-year corporate bond at “+35 bps to the 2-year.” This means they will buy from or sell to you the security at a yield which is 35 basis points higher than the yield to maturity on the 2-year US Treasury Note. So, if the quote is “+75” when the comparable Treasury has a yield of 3.25%, the corporate bond will yield 4.00%. By the way, don’t both look for those spreads and yields at this time

So, how goes the US Treasury market is how goes the domestic bond market, in general. In other words, the Treasury market essentially sets the long-term price of money in the United States. After all, that is all interest rates are: the price of money. If our Econ 101 classes taught us anything, it is supply and demand ultimately determine the price of anything.

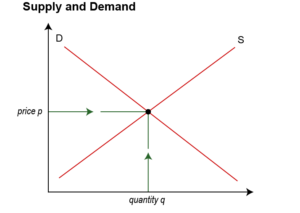

Consider the following standard supply/demand curve graph.

In this instance, assume the supply curve (S) is the supply of US Treasury securities available to investors. Obviously, D will be investor demand for them. The point where the curves intersect is the market price, or market equilibrium where supply is equal to demand.

If you can conceptualize such things, the price will increase when either demand increases or supply decreases. Conversely, prices will go down when demand goes down or supply increases. This is sort of intuitive, but we economic types like to make things as difficult as is possible.

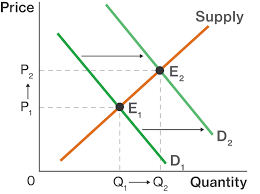

Since there is an inverse relationship between bond prices an interest rates, this means yields will fall (prices go up) when investor demand is greater than the supply of securities available. As amazing as it may sound, this has been what has happened even as the US public debt has mushroomed over the last decade: although the supply of debt (bonds/fixed income) has exploded, investor demand has grown even faster. As a result, interest rates have fallen as prices have risen.

Since there is an inverse relationship between bond prices an interest rates, this means yields will fall (prices go up) when investor demand is greater than the supply of securities available. As amazing as it may sound, this has been what has happened even as the US public debt has mushroomed over the last decade: although the supply of debt (bonds/fixed income) has exploded, investor demand has grown even faster. As a result, interest rates have fallen as prices have risen.

It really is good, old-fashioned supply & demand.

However, if that is too nerdy for you, consider this little analogy to help explain why bond prices fall when interest rates rise.

Imagine a pizza parlor sells a 10” cheese pizza for $10, a 12” pie for $10, and a 16” one for, again, $10. Which one would you choose?

If you are like most people, you would choose the 16” one for one simple reason: why pay the same amount for less? After all, leftovers can be good.

However, if that is too nerdy for you, consider this little analogy to help explain why bond prices fall when interest rates rise. Imagine a pizza parlor sells a 10” cheese pizza for $10, a 12” pie for $10, and a 16” one for, again, $10. Which one would you choose? If you are like most people, you would choose the 16” one for one simple reason: why pay the same amount for less? After all, leftovers can be good.

With this in mind, imagine you have to choose between 3 different bonds which are equal in all measures except the coupon. One pays 4%, another pays 2%, and the last one yields 6%. Which one should be the most expensive, again all other things being equal? Which one should be the least and which one should be in the middle? You don’t have to be a bond trader to rank them from most expensive to least as: 6%, 4%, and 2%. Again, why pay the same amount for less?

With this primer out of the way, the current levels of interest rates likely aren’t sustainable, long-term, due to a variety of factors. First, much of the recent spike in demand for US debt has been from the Federal Reserve. The US monetary authority, in an effort to keep the financial markets flush with cash, has been on a buying spree, paying for securities with ‘money’ which previously didn’t exist. Since 2007, the Fed has grown the size of its balance sheet from roughly $900 billion in assets at the end of that year to over $8 trillion by the 2nd quarter of 2021.

As I type here in August 2021, the Fed is continuing to add an additional $120 billion to its asset base each month. You don’t have to be a PhD in calculus to know that works out to be more than $1 trillion per year, which is a lot of money. Intuitively, this won’t, or shouldn’t last forever, without causing problems to the overall economy when the sheer supply of money (or potential for it) swamps demand.

Secondly, foreign demand for our debt has been rampant over the last two decades. At the end of the 2nd Quarter, international investors owned a whopping $7.202 trillion worth of US Treasury debt. Since everything is essentially priced off the Treasury market, this strong demand for our debt has caused the price of money in the US economy to fall.

But why has the demand been so robust?

Some countries want to keep their currencies weaker than they would be ordinarily against the US dollar in order to make their exports to our country less expensive. For others, the US is a more attractive investment risk than their own markets due to the liquidity in our financial system and the dynamism of our economy. At some point, intuitively: 1) export driven economies will become wealthier and start to demand more imports, and; 2) the return gap between our economy and the rest of the developed world will narrow.

Finally, and it seems like people have been saying this for years, investors will eventually refuse to continue to buy debt which doesn’t keep up with the expected rate of inflation. While we aren’t supposed to make guarantees or promises in the investment industry, I will promise you this: IF you purchase a 10-year bond which has a yield to maturity of 2%, and inflation averages 3% over the next decade, the purchasing power of your total cash flows will decline. In other words, you will lose money in relative terms, and why would you do that for an extended period of time when there are numerous alternative investments and mountains of stuff to buy?

That is a great question.

So much so, the Investment Committee has had a hard time finding value in the bond market, in general. There is simply too much interest rate risk and too little return potential. The question isn’t IF interest rates will head in the opposite direction at some point, the question is when, particularly since Americans historically like to take risks and hate having money burn holes in their pockets.

This leads to the following last piece of the puzzle: when will all of this occur?

Although I actually do have a crystal ball in my office, it is impossible to predict the future with perfect clarity. However, the easy money, the low hanging fruit if you will, is when the Federal Reserve starts to reduce the size of its monthly purchases.

That doesn’t mean rates will start to spike on that day. It simply means the bond market won’t have the tailwind of the Federal Reserve’s arguably artificial demand, at least not to the same level. You can think of it is as the first drop in the bucket.

In fact, interest rates could very easily fall when the Fed finally announces the so-called ‘tapering of asset purchases.’ This will be due to worries about a potential short-term decline in the economy, as opposed to a longer-term view about the demand for money in the US, which should start to decrease. IF Washington can’t get a handle on its spending, and therefore the supply of debt, I think you get the picture: supply will eventually grow faster than the demand for US debt, in general, and the price of money will increase as a result. Borrowers will simply need to get paid more to part with their cash.

So, what to do? First, and most importantly, stay short. By this, I mean stick to securities with a short time until maturity during a rising interest rate environment. They will lose less of their value than those with longer maturities. There is a lot of math involved here, discounting the present value of future cash flows and all that jazz, so just trust me. Second, as always, do your credit work to determine how a particular bond will perform as rates rise. Third, ladder bond maturities in order to have a systematic way to capture rates as they go higher. Finally, if you just have to have some fixed income as rates are rising, corporate bonds will probably be the most attractive of all unattractive bond sectors.

In the end, when rates rise, bonds should lose their value, all other things being equal. It is nothing more than math, Econ 101, and maybe even a quick trip to the pizza joint. To that end, I have learned a lot about bonds over the last three decades, and, as I am sure you will agree, I have also learned how to make some pretty corny analogies, or should I say cheesy. Hopefully, this combination can sometimes help get the message across.