Section I

According to the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business datasets, the number of publicly traded companies in the US has been falling like a stone, from a high of 7,439 in 1996 to 3,616 in 2017. Obviously, this has had some kind of an impact on the markets and benchmark index construction. But how much? Is it good or bad? What does it mean to the health of the US financial system?

First things first; fewer publicly traded stocks means fewer available options for investors. The money has to go somewhere, right? Almost by definition, some firms are larger than they would be IF there were still double the number of stocks on the various exchanges. While these would probably be more heavily concentrated towards the lower end of the market capitalization range, the fact remains: all other things being equal, the slices will be bigger if I cut a 16” into 6 instead of 12.

Of course, some of you would argue I could make one or a few stocks super huge and keep the remainder the same, and you know who you are. There are a myriad of possible ways to cut the thing. THAT is the reason why I wrote “all other things being equal.”

However, there has never been more money in the stock market than there currently is. So…more capital chasing fewer options? Hmm. The actual supply of stocks going down while demand is going up? By definition, what happens to prices, in general?

In essence, you could make a reasonably sentient/coherent argument the markets can support elevated valuations due to the relative paucity of equity availability. Couple this the low absolute level of interest rates AND contemporary investors’ propensity to buy passive investment alternatives, and, voila! You have the ingredients for what some would call an outrageously priced stock market!

If you want an even more dumbed down explanation, try this one on for size: the money has to go somewhere. Indeed it does.

….but, is the US market healthy IF that number of stocks have disappeared, if disappear is the right word? Now, that is a great question, and the answer is yes.

You see, companies typically go public to: 1) provide liquidity for investors, and; 2) raise capital they couldn’t have otherwise. Not so long, a public offering was arguably the most effective way of doing this, if not the only way for a lot of companies. The regulatory burden was a small price to pay, seemingly so, for the benefits of being public. The markets have changed.

These days, investors are far more comfortable with the concept of ‘private equity.’ In fact, a lot of sizable institutional pots of money, like public retirement funds and university endowments, have a target allocation for private equity. As a result, there is more money chasing private companies than previously, AND the money ain’t just the local usual suspects.

So, IF a company can provide liquidity for its shareholders AND raise capital privately, why would it go to the hassle of going public? More regulators and arbitrary earnings estimates? Having Wall Street help shape your business model? Seeing how one bad quarter can erase years of good ones? Yes, why indeed go public?

Hmm. Staying private makes some sense, particularly now that investors are more comfortable provided the necessary cash. But, how can both public and private equities be soooo hot right now? It would seem as though they would crowd each other out. Right? After all, there will be a finite amount allocated to equities in aggregate, right?

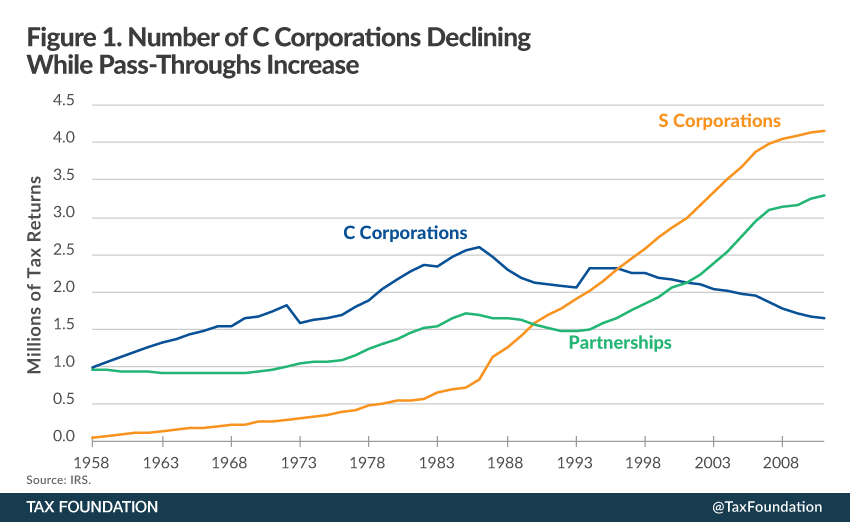

Consider this chart which I lifted off the Tax Foundation’s website.

You know, sometimes a picture IS worth a thousand words. Or should I say trillions of dollars in market capitalization.

I won’t bore you with all the details. C corporations are the traditional ‘option’ for non-affiliated/outside investors looking for private equity for their portfolio. Now, notice the trend in the chart above. What is going on there? It would appear as though there are 1 million fewer C corps than in the early 1980s, doesn’t it? Huh. Meanwhile, the number of S corporations and partnerships have soared!

Fewer publicly traded options and fewer private options for the average ‘outside’ investor? This is absolute terms while the number of investors AND the amount of global capital has soared. What is the logical, or illogical, outcome? Again, what does the law of supply and demand suggest?

In the end, what if (and this is just a question) investors will have to just have to put up with higher valuations because of, well, the US tax code and regulatory environment? If the IRS and regulators want to limit the number of investment options available to equity investors, what can we do?

Section II

This past week, I read an interesting article which speculated why workers’ wages have not grown as fast as the economy and corporate profits over the last couple of decades. While we have come to accept the argument technology has made US workers both more productive and redundant, the writer’s contentions were decidedly less clever: employers have less competition than they previously did.

Frankly, this make more sense than the technology line of reasoning. Using a somewhat close to home example: if the Georgia Pacific Naheola Pulp & Paper Mill in Pennington, Alabama, shuts down, the unemployment rate in Choctaw County will shoot through the roof, and in a hurry. According to advantagealabama.com, that one employer accounts for about a quarter of the jobs over there. That sort of thing.

For grins, how about another one? Down the road a ways in Bullock County, it seems as though two employers, Wayne Farms and Bonnie Farms, account for close to 60% of private sector jobs. This is called an oligopsony, and Merriam-Webster defines one as: “a market situation in which each of a few buyers exerts a disproportionate influence on the market.”

To be sure, it may seem like we have a lot of choices, but do we really? Consider the domestic airline industry. You can get to anywhere in the world. Just go over to, say, the Montgomery Regional Airport; get on a plane; make a connection or two, and pay whatever Delta or American demand you pay. Take it, leave it, or drive to Atlanta. Does that sound familiar to anyone?

Or what about soft drinks? Three companies dominate the industry: Coca-Cola, Pepsi, and soon to be Keurig Dr. Pepper. Beer? Two firms control roughly 70% of the market: Anheuser-Busch InBev and Miller Coors. Ever been to a small town with a Walmart? Brother, lots of stuff to buy and a lot of empty storefronts. I will spare you other examples, but, suffice it to say, we have a lot of products from which to choose but relatively few companies. Guess what? Corporations consume things too, such as labor.

Almost without realizing it, we have created a buyers’ market for labor throughout much the country. This has helped set a de facto ceiling for wages outside of our more dynamic local economies, especially in rural areas. Simply put, employers don’t have to compete for workers, or at least not very hard. If you don’t like what they are offering, someone else will come along later who will.

But we have known this for a long time in Alabama, haven’t we? When the mill or mine shuts down, the town often does too. This type of thing has led to a gutting of small towns across the country, and not just in our state. Some will thrive, some will die, and the rest will just kind of limp along. The get up and go will get up and leave, and only the extreme haves and have nots will remain. The former has no reason to change the system, and the latter doesn’t have the ability.

It is kind of depressing really, but it isn’t necessarily a macroeconomic problem. Capital will flow to its highest and best use and location. The end result will eventually be more goods and services than we have ever had. Hasn’t that been the way it has worked for some time now?

In the end, I suppose you could argue wage stagnation and shuttered small towns are the rewards we reap when we put corporate efficiencies, profits, and materialism over community. Consider this, and make your next purchases accordingly.

Take care, and have a great weekend.

John Norris